The Shakespeare’s Head

July 13, 2011

At 29 Great Marlborough Street, W1 (but most often approached by Carnaby Street, where it’s situated on a corner where the street meets Fouberts Place) stands The Shakespeare’s Head.

The sign outside the pub claims the inn was established on the site in 1735 and was named after the owners, Thomas and John Shakespeare, who claimed to be distant relations of their famous namesake. Nothing of the original establishment remains – the building which stands today is late nineteenth-century (albeit in a Tudor style) – and there are serious doubts over whether it has any connection even with Shakespeare’s descendants. After all, The Shakespeare’s Head is a fairly common pub name in London – others can be found in Holborn, the City, Kingsway, Finsbury and Forest Hill.

It’s likely Thomas and John Shakespeare form part of a colourful story about the pub’s origins, and one which has been stated with increasing conviction over the years. The presence of the claim on a nicely-painted board outside the pub certainly helps attract the passing tourists ambling down Carnaby Street, but it doesn’t make the story any more likely to be true.

What the pub does have, however, is one of London’s most charming Shakespeare statues.

There are others dotted around the capital – Leicester Square, Westminster Abbey, on the front of City of London school, a bust in the churchyard of St Mary Aldermanbury – but none with the playfulness of the one which peers out from a window-like recess of the pub.

There’s just something perfectly realised about the position of the body. While the face is cold and fixed, the stance of the body really conveys him casually examining the crowds below – a fixed moment where the greatest playright of all time is half-looking for inspiration in the throng that passes outside his window.

I have no idea whether the bust has always been painted in these cold colours, but there’s more than a touch of “zombie Shakespeare” about the hue (a zombie Shakespeare made an appearance in The Simpsons’ 1992 Halloween special Treehouse of Horror III, looking surprisingly similar to the pub’s statue.)

The sign outside also claims the bust lost a hand in World War 2 “when a bomb dropped nearby.”

While the bust is definitely one hand down, I’m inclined to take everything that sign says with a pinch of salt.

The Men Who Wrote Shakespeare

May 4, 2011

Whether one believes a barely-educated glove-maker’s son from Stratford-Upon-Avon could produce the greatest single body of literature in the history of the world or not (and if you want to find yourself unsure, John Mitchell’s excellent Who Wrote Shakespeare? (1996) will give you plenty of conspiracy food for thought), one fact is unassailable: the man known as Shakespeare didn’t write the plays which we can pick up and read today.

That’s not to say the words weren’t his – but if William Shakespeare ever physically wrote any of those words down, nothing has survived. Instead, the plays we know today as ‘Shakespeare plays’ are the work of two men who have been largely forgotten: the actors John Heminge and Henry Condell.

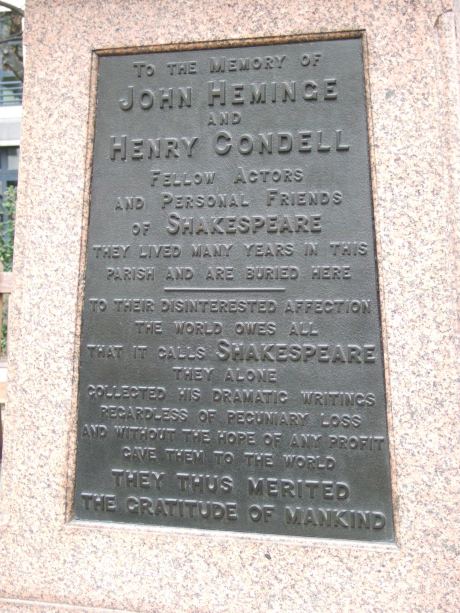

I say ‘largely forgotten’, but in the City churchyard of St Mary Aldermanbury, EC2, is a memorial dedicated to them both.

While the bust of Shakespeare sits proudly on top of the memorial, the plaques on the main body are dedicated to Condell and Heminge.

The text reads:

To the memory of JOHN HEMINGE and HENRY CONDELL, fellow actors and personal friends of SHAKESPEARE. They lived many years in this parish and are buried here.

To their disinterested affection the world owes all that it calls SHAKESPEARE. They alone collected his dramatic writings, regardless of pecuniary loss and without the hope of any profit, gave them to the world.

THEY THUS MERITED THE GRATITUDE OF MANKIND.

The two were Shakespeare’s co-partners at the Globe theatre in Southwark, and on his death in 1616

from the accumulated [plays] there of thirty five years, with great labour selected them. No men then living were so competent having acted with him in them for many years, and well knowing his manuscript, they were published in 1623 in Folio, thus giving away their private rights therein. What they did was priceless, for the whole of his manuscripts with almost all those of the dramas of the period have perished.

There’s no question of an authorship controversy here. The two men state unequivocably that Shakespeare was the author of the plays at a time when many of his contemporaries were still alive. It is one of the strongest refutations ofthe idea Shakespeare was not their author.

If it wasn’t for Heminge and Condell, the works of Shakespeare could have been lost to the world forever. They were the fine thread between us having the work of the world’s greatest writer and it being lost entirely.

How different the world would be if they hadn’t sat down one day, with a pile of dusty papers and half-remembered passages they’d performed a decade before, and thought, “Well, maybe we should try and get the lot of them written down for posterity.” It starts to make me feel ill at the thought of the great works that have been lost forever simply because there was no Heminge or Condell around to save it.

Everytime someone performs a Shakespeare play, there should be a round of applause at the start for the men who ensured that Shakespeare’s words survived.

The Church of St Mary Aldermanbury no longer stands, but was first mentioned in 1181 and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren following the Great Fire of London in 1666. Bombed during the Second World War, the stones were removed in 1966, shipped to America, and the church was rebuilt in the grounds of Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. It was erected as a memorial to Winston Churchill, who had given his famous ‘Iron Curtain’ speech in the Westminster College gymnasium in 1946.