O’erwhelmed with gore! The transport death pioneers of Harrow

October 19, 2012

As a child growing up in nearby Hatch End, the gravestone of John Port was always a highlight of a visit to St Mary’s Church in Harrow On The Hill.

On the afternoon of 7 August 1838, Port was a guard on the London to Birmingham train and as it travelled through Harrow, he slipped and fell while walking between the carriages to check tickets. Both his legs were severed as the train went over him and he died later that day from massive blood loss.

The coroner’s inquest found that:

the unfortunate deceased started with the Denbigh Hall five o-clock train on Tuesday last from the station at Euston grove, and having arrived within a mile and a quarter of Harrow, as was the usual custom, he dismounted from his seat for the purpose of collecting from the passengers what is termed the ‘excess fares.’ … In the performance of this duty the deceased was engaged on Tuesday, which compelled him to pass from one carriage to the other by the steps, and when in the act of placing his foot on one of them, at the time the train was proceeding at upwards of thirty miles an hour, his foot slipped between the wheels, which as they successivley passed over, dragged his legs in, crushing them inch by inch up to one of his knees and above the other.

His tombstone bears a gruesome poetic account of the incident.

- TO THE MEMORY OF

- THOMAS PORT

- SON OF JOHN PORT OF BURTON UPON TRENT

- IN THE COUNTY OF STAFFORD, HAT MANUFACTURER,

- WHO NEAR THIS TOWN HAD BOTH HIS LEGS

- SEVERED FROM HIS BODY BY THE RAILWAY TRAIN.

- WITH THE GREATEST FORTITUDE HE BORE A

- SECOND AMPUTATION BY THE SURGEONS, AND

- DIED FROM LOSS OF BLOOD.

- AUGUST 7TH 1838 AGED 33 YEARS.

- Bright rose the morn and vig’rous’ rose poor Port.

- Gay on the Train he used his wonted sport:

- Ere noon arrived his mangled form they bore,

- With pain distorted and o’erwhelmed with gore:

- When evening came to close the fatal day,

- A mutilated corpse the sufferer lay.

Over the years, the headstone has eroded to the point of near illegibility, despite being Grade II listed in 1983.

Port’s death came only eight years after the first ever British rail fatality, that of William Huskisson MP, who died in similar circumstances.

At the opening of the Manchester to Liverpool railway, he “lost his balance in clambering into the carriage and fell back upon the rails in front of the Dart, the advancing engine” which then ran over his leg, severing it. Huskisson died of blood loss, having “lingered in great agony for nine hours.”

Surprisingly, there is also a memorial nearby for another transport-fatality pioneer.

Two minutes stroll down the hill, on the corner of Grove Hill, is a plaque commemorating the first car driver ever to die in a road accident.

The driver, Mr E.R. Sewell had been demonstrating the vehicle, a Daimler Wagonette, to 63-year-old Major James Stanley Richer, Department Head at the Army & Navy Stores, with the view to a possible purchase for the company.As they drove down the hill at 14mph, a wheel shed it’s rim. Both Sewell and Richer were thrown from the car onto the road.

Sewell died instantly, and when Major Richer died four days after the accident without regaining consciousness, it became a dubious double-first – the first death of a driver in Britain, followed by the first death of a passenger in a car

The dubious accolade of being the first person to be killed by a car in Britain goes to Mrs Bridget Driscoll of Old Town, Croydon who on 17 August 1896 was run over by a Roger-Benz car while attending a folk dancing festival at Crystal Palace.

The driver was going at 4 mph (described by witness as “a reckless pace”), and at Mrs Driscoll’s inquest, Coroner William Percy Morrison said he hoped that “such a thing would never happen again.” He was also the first to apply the term ‘accident’ to violence caused by speed.

Since then, some 30 million people have lost their lives in car accidents, but a woman from Croydon is the name which appears at the very top of the list.

The Men Who Wrote Shakespeare

May 4, 2011

Whether one believes a barely-educated glove-maker’s son from Stratford-Upon-Avon could produce the greatest single body of literature in the history of the world or not (and if you want to find yourself unsure, John Mitchell’s excellent Who Wrote Shakespeare? (1996) will give you plenty of conspiracy food for thought), one fact is unassailable: the man known as Shakespeare didn’t write the plays which we can pick up and read today.

That’s not to say the words weren’t his – but if William Shakespeare ever physically wrote any of those words down, nothing has survived. Instead, the plays we know today as ‘Shakespeare plays’ are the work of two men who have been largely forgotten: the actors John Heminge and Henry Condell.

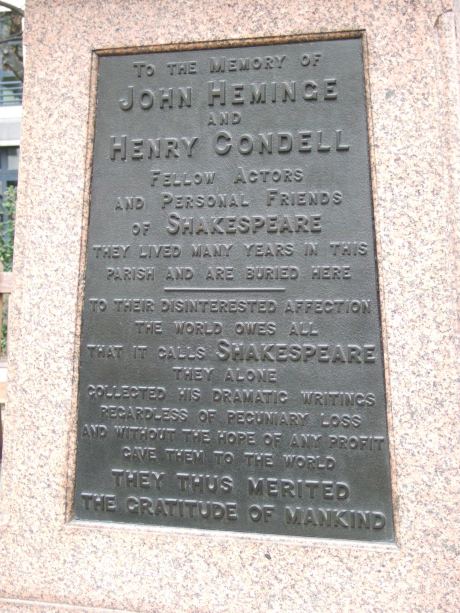

I say ‘largely forgotten’, but in the City churchyard of St Mary Aldermanbury, EC2, is a memorial dedicated to them both.

While the bust of Shakespeare sits proudly on top of the memorial, the plaques on the main body are dedicated to Condell and Heminge.

The text reads:

To the memory of JOHN HEMINGE and HENRY CONDELL, fellow actors and personal friends of SHAKESPEARE. They lived many years in this parish and are buried here.

To their disinterested affection the world owes all that it calls SHAKESPEARE. They alone collected his dramatic writings, regardless of pecuniary loss and without the hope of any profit, gave them to the world.

THEY THUS MERITED THE GRATITUDE OF MANKIND.

The two were Shakespeare’s co-partners at the Globe theatre in Southwark, and on his death in 1616

from the accumulated [plays] there of thirty five years, with great labour selected them. No men then living were so competent having acted with him in them for many years, and well knowing his manuscript, they were published in 1623 in Folio, thus giving away their private rights therein. What they did was priceless, for the whole of his manuscripts with almost all those of the dramas of the period have perished.

There’s no question of an authorship controversy here. The two men state unequivocably that Shakespeare was the author of the plays at a time when many of his contemporaries were still alive. It is one of the strongest refutations ofthe idea Shakespeare was not their author.

If it wasn’t for Heminge and Condell, the works of Shakespeare could have been lost to the world forever. They were the fine thread between us having the work of the world’s greatest writer and it being lost entirely.

How different the world would be if they hadn’t sat down one day, with a pile of dusty papers and half-remembered passages they’d performed a decade before, and thought, “Well, maybe we should try and get the lot of them written down for posterity.” It starts to make me feel ill at the thought of the great works that have been lost forever simply because there was no Heminge or Condell around to save it.

Everytime someone performs a Shakespeare play, there should be a round of applause at the start for the men who ensured that Shakespeare’s words survived.

The Church of St Mary Aldermanbury no longer stands, but was first mentioned in 1181 and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren following the Great Fire of London in 1666. Bombed during the Second World War, the stones were removed in 1966, shipped to America, and the church was rebuilt in the grounds of Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. It was erected as a memorial to Winston Churchill, who had given his famous ‘Iron Curtain’ speech in the Westminster College gymnasium in 1946.