Bud Flanagan in Hanbury Street, E1

June 22, 2012

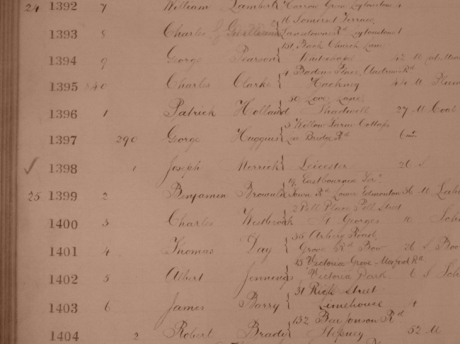

Chaim Reeven Weintrop was born at 12 Hanbury Street (just off the Commerical Road) on the 14th October 1896 to Polish-born Jewish parents “who had been in the country for years [but] could hardly be understood when speaking English.”

The Registrar chose to anglicise the name, alien-to-his-ears, to ‘Robert Winthrop’ – but it was under a third name that the boy would one day gain national stardom.

Leaving the poverty of the East End at 14, as a stowaway on a ship bound for America, Winthrop slowly wriggled his way into the vaudeville circuit as a low-ranking black-face comic. He toured America, Australia and South Africa (with limited success) before returning to Britain to enlist at the start of the First World War.

Winthrop’s better-known stage name was supposedly chosen after he endured bullying from a vicious sergeant. As soon as he was demobbed, he is supposed to have told the superior officer that one day, he’d make his name a joke and everyone would laugh when they heard it. The sergeant’s name was Flanagan. If the story’s true, he certainly succeeded.

In the 1920s, his partnership with a better-known straight actor named Chesney Allen started to make Bud Flanagan a star.

In the 1920s, his partnership with a better-known straight actor named Chesney Allen started to make Bud Flanagan a star.

Dressed in a moth-eaten fur coat while Allen looked dapper and smart, Bud composed their signature song Underneath the Arches, had a hit with the timeless Run Rabbit Run, coined his yelped catchphrase “Oi!” (which he shouted to cover up any words he fluffed on delivery, and was immediately echoed by the orchestra) and his popularity with the Royal Family paved the way for the Royal Variety performances.

Flanagan backstage at a Crazy Gang show with guest Charlie Chaplin

The duo’s numerous live shows with fellow double-acts Nervo and Knox, Noughton and Gold and solo act ‘Monsewer’ Eddie Gray saw them billed as the Crazy Gang – a kind of dream team of comedy – and their shows repeatedly sold out West End theatres for two-year-long runs from 1937 until the late 1950s (their final performance was in 1961.)

Sadly, not a lot of footage of them exists and the films they made are hard to find, but this clip from 1937’s O-Kay For Sound shows them in their later prime, and brings home how much Morecambe and Wise and the Carry On teams owe to the Crazy Gang. The business with the hat being accidentally knocked off time and time again just doesn’t age.

Flanagan remained a huge favourite until his death in 1968. Perhaps his best-known legacy today is the last job he performed in his final days: singing (in his melancholic nasal London twang) the theme tune for Dad’s Army, ‘Who Do You Think You Are Kidding Mr Hitler’ – a song which doesn’t date from the war, but was especially written for the TV show in the style of Flanagan’s war-time ditties (you can relive it here.)

Flanagan was cremated at Golder’s Green where he has a plaque – and his death was such a national event that his funeral was filmed by British Pathe. At 58 seconds in, Chesney Allen arrives – ironically, their working partnership was ended by Allen’s ill-health, although he would go on to outlive Flanagan by 14 years.

But unlike many of the performers of his generation, who were nostalgic for the London of their youth, Flanagan (who for a good stretch of years was the single most recognisable comedian in the country) looked back on where he’d come from later in life not with rose-tinted spectacles and rags-to-riches-nostalgia, but a mix of bitter amusement and abject disgust.

In his 1961 autobiography My Crazy Life, Flanagan was surprisingly frank about his feelings towards Hanbury Street.

At the time of his birth, the area was synonymous (and a century later, it could be argued it still is) with the murders perpetrated by Jack The Ripper.

In 1888, the body of one of the victims, Annie Chapman, was discovered in the backyard of no.29. Discovered in the early hours of the morning, the enterprising neighbours in the road of dosshouses had opened their doors by the middle of the day, charging admission for a better view of the bloodstain in the yard. Supposedly a bit of a party atmosphere began, with sightseers making a day of it and the pubs doing a roaring trade as the rubberneckers went back and forth.

Choosing that anecdote to set the scene, an aging Flanagan vividly painted a picture of his childhood home:

Hanbury Street crawled rather than ran from Commercial Street, where Spitalfields Market stood at one end, to Vallance Road, an artery that spewed itself into Whitechapel Road at the other. On one corner stood Godfrey Phillips; tobacco factory, with its large, ugly enamel signs, black on yellow, advertising “B.D.V” – Best Dark Virginia. It took up the whole block of the first turning, a narrow lane with little houses and a small sweet shop. This was known as Corbett’s Court. There is today a luxury block of flats in Kensington with the same name. I smiled as my memory went back to the Corbett’s Court I knew. The only luxury about it wa the rent of houses – 3s. 6d. a week.

On the next corner was a barber’s shop and a tobacconist’s which my father owned. Next door to us was a kosher restaurant with wonderful smells of hot salt beef and other spicy dishes, then came the only Jewish blacksmith I ever met. His name was Libovitch, a fine black-bearded man, strong as an ox. From seven in the morning until ten at night, Saturdays excepted, you could hear the sound of hammer on anvil all over the street. Horses from the local brewery, Truman, Hanbury and Buxton, were lined up outside his place waiting to be shod.

Then came another court; all alleys and mean streets. Adjoining was Olivenstein, the umbrella man, a fruiterer, a grocer, and then Wilkes Street. On one side of it was a row of neat little houses and on the other the brewery, taking up streets and streets, sprawling all over the district. On the corner of Wilkes Street stood The Weaver’s Arms, a public house owned by a Mrs Sarah Cooney, a great friend of Marie Lloyd. She stood out like a tree in a desert of Jews. It wasn’t a couple of hundred yards from Commercial Street, with its busy fruit market and rattling horse trams.

Stapleton’s Repository, where horses were bought and sold, eas next door to a fried fish shop, Number 14 Hanbury Street, where I was born. Next door was Rosenthal, tailors and trimming merchants, then a billiard saloon; after that a moneylender’s house where once lived the Burdett-Coutts.

Hanbury Street was a patchwork of small shops, pubs, church halls, Salvation Army hostels, doss houses, cap factories and sweat shops where tailors with red-rimmed eyes sewed by gas-mantlelight. It was typical of the Jewish quarter in the ‘90s. The houses were clean inside, but the exteriors were shoddy. The street was narrow and ill-lit. The whole of the East End in those days was sinister…

It was a very tough neighbourhood; in fact, it was Jack the Ripper’s slay ground. They tell a story of a man walking along Hanbury Street when a heap of rubbish fell on his head. He looked up and there was a kid leaning out of his window laughing like hell. The man shook his fist and shouted, “Come down, you little bastard, and I’ll kill you.” The kid laughed and said, “Come down? I can’t even walk yet.” That gives you some idea of the district…

Ours was a district where the weak went to the wall, and you had to keep your eyes open. When my father opened his fried fish shop, the salt cans were chained to each table – and to the counter.

Flanagan performed for the first time as a child in his father’s shop in 1908, demonstrating a magic act.

When the fish shop was closed on a Sunday, I let the kids in for a farthing, charged the older ones a ha’penny and gave them a show. Mothers would bring the children, and soon there was a sprinkling of grown-ups. I was making a local name until one Sunday, a big rat came out of nowhere and evil-eyed the audience. There were screams, and before you could say abracadabra, the place had emptied. It not only did me harm, but word soon spread, “There are rats in the fish shop”, which was not surprising as we were next to a horse repository, with its hay and oats. There wasn’t a morning when the traps had fewer than three or four big ones. I used to watch in fascinated horror as they drowned in a deep tub of water.

A blue plaque to Flanagan is on the front of the house, and two doors away is Poppies, a thriving fish and chip shop (which, while old, is not the one Flanagan’s father ran. Let me stress, it’s 100% worth a visit though. Delicious.)

A Tesco Far, Far Away

January 3, 2012

The vast Tesco in Borehamwood is probably the most famous supermarket in the London area.

Walking into it – and it’s more like walking into a small town than a supermarket – there’s little clue as to its claim to fame. But looking around, there are one or two hints.

On top of the covered walkway leading up from the huge, featureless car park is an unusual weather vane.

And if you look to your left when you reach the doors, there’s a much larger clue.

Before the mammoth Tesco was built, the site formed the backlot of Elstree Studios – the most important film studio in Britain during the 1960s and 1970s and today most famous as the location where the original Star Wars trilogy was filmed.

The image below shows the studios at the time Star Wars was filmed – to the right of the red line is where the Tesco stands today, while on the left is what remains of the studios, all largely untouched.

Opened in 1925 as the First National Studios by American JD Williams (who bought the site when it was informed it was “free of fog”), the 50 acres making up Elstree Studios are actually not located in Elstree, but Borehamwood. At the time, Borehamwood was little more than a few houses and a pub, so the railway station in the centre was named ‘Elstree’ after the better known nearby village (the station’s name eventually changed to Elstree and Borehamwood to reflect the town’s growth.)

In 1929, the first British talkie was produced at the studios – Blackmail, directed by a 30-year-old Alfred Hitchcock. A parallel silent version was also made, which proved more popular at the time, due to a lack of cinemas with the technology to broadcast the soundtrack.

As Elstree Studios – and the five rival studio complexes which sprang up in its wake – brought work to the area, Borehamwood grew into a larger town. It was dubbed the ‘British Hollywood’ during the 1950s and 1960s, when films including The Dam Busters, Look Back in Anger, Cliff Richard’s The Young Ones and Summer Holiday, Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita and Ice Cold In Alex were filmed in the six studios, side by side with a host of hugely successful TV series including The Avengers, Jason King, The Saint, The Champions and Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased).

In the early 1970s, the studio work started to slowly dry up – classic films like The Railway Children and A Clockwork Orange gave way to On The Buses and the Confessions of a Window Cleaner series, and the TV dramas deserted the studios for location shoots, taking a page out of the book of ITV’s hugely popular The Sweeney.

The similarly struggling Hammer production company moved from Bray to Elstree in 1967, and made a series of movies at the studios until they slid into bankruptcy in 1979. Aside from a handful of late classics (such as Quatermass and the Pit and One Million Years BC, remembered more for Raquel Welch’s fur bikini than anything else), the Elstree-vintage Hammer films began to ramp up the gore and nudity as the censors relaxed the code, and they had to compete with more gruesome horror fayre from America and Italy. 1976’s Dennis Wheatley adaptation To The Devil A Daughter was the final Hammer film made at the studios and it largely disappeared without trace at the box office.

The struggling studios were thrown a lifeline in 1975, when George Lucas decided to film Star Wars at Elstree (the first shot of the film was recorded in Studio 8, which is still standing today – when I was there, the ITV show Dancing On Ice was being loaded in.)

It was simply a stroke of good luck out of bad. Fox had little faith in the supposedly ‘dead’ genre of sci-fi, so wanted to hire somewhere cheap for what they thought would undoubtedly be a money-loser. Elstree’s studios were not just big enough to accommodate the massive scale of Lucas’s pre-CGI vision, but they were also empty and available at rock-bottom prices. And it wasn’t just Fox that had no faith in Lucas’s movie being a success – Elstree Studios were offered a flat-fee or a percentage of the profits of the film, and immediately plumped for the flat-fee.

Lucas returned again in 1979 to make The Empire Strikes Back, in 1982 to make Return of the Jedi, and over the years Willow, Labyrinth and the Indiana Jones series (having been taught a lesson about underestimating Lucas’s money-making ability by taking a flat-fee instead of a profit share with Star Wars, the studio amazingly rejected exactly the same offer when he made Raiders of the Lost Ark.) It was the era of the big studio-bound spectacular, and it would mark the high watermark of Elstree’s fortunes.

Lucas’s contribution to the studio’s fortunes are commemorated in the massive George Lucas Stage which was built in 1999, overlooking the Tesco where his movies were made. Popular legend has it that the scenes set on the ice planet of Hoth were filmed where Tesco’s frozen food aisle now sits. Inside, the corridors running between the huge cavernous studios are almost entirely featureless. It’s not exactly a magical place.

In 1978, Kubrick filmed The Shining at Elstree, building the entire Overlook Hotel interior on Stages 3 and 4, with the exterior constructed on the backlot, with mountains of salt standing in for snow. It all now forms part of Tesco’s car park.

In a bizarre piece of trivia, one of the runners on the film was a local boy from Elstree named Simon Cowell, who would go on to international fame twenty years later. Although none of his TV shows were filmed at Elstree, there is now a prominent plaque to Cowell outside – the first film he worked on was The Return of the Saint, so it’s at least tangentially appropriate that his tribute is next to one for Roger Moore.

Despite these bright spots, the productions were sporadic, and the studios went through a number of different owners through the years. The other studios amalgamated, moved or wound-up; today, only Elstree Studios and BBC Elstree (the long-term home of Eastenders) remain.

In 1988, following numerous takeovers and an ongoing decline in revenues, the studios were bought by the property developer Brent Walker, who had dabbled in movies under the Goldcrest name. Under the guise of modernising and compacting the virtually derelict studios, they demolished six of the nine studios and sold the entire (now empty) backlot to Tesco. Despite a pledge to operate the studios for 25 years, Brent Walker ran into financial difficulty and decided to close the doors in 1995.

For three years, they tried to sell off the derelict site for use as a shopping centre, with the main opposition to their plan coming from a local campaign named Save Our Studios, run by the council’s Entertainment Officer Paul Welsh. As a lifelong film buff and Borehamwood resident, Welsh had seen at first hand how the industry failed to preserve or value its own heritage. He told the Elstree Studios website:

I’ve seen things thrown into skips that you could cry about. I’ve seen scripts discarded, props from Star Wars that would cost a fortune now to buy abandoned, documents from Hitchcock’s Blackmail dumped into a skip. In the late sixties they had a library of screen tests that they’d done on actors of the 1930s. Richard Harris, Audrey Hepburn, Laurence Olivier, a whole cast of people who’d gone through the studio, and an executive of the time just stopped by and said, ‘what’s the purpose of keeping the junk?’ and they just scrapped it all.

Partly due to the pressure from Walsh, Brent Walker sold the site in 1996 to Hertsmere Borough Council for £1.9million. Since then, the studios have been renovated, and the TV side rejuvenated. Within a decade, the studios were the home of Who Wants to Be A Millionaire and the Big Brother house, which moved from East London into a vast sunken water tank at the back of the studios, which was originally constructed for 1955’s Moby Dick.

In recent years, the movies have also returned, with recent productions at Elstree including The King’s Speech, Saving Private Ryan, Batman Begins, The Other Boleyn Girl, Notes on A Scandal, Tomorrow Never Dies and Kick Ass.

The town’s fortunes have always been linked to the rise and fall of the nearby studios, and the long, steady decline in the British film industry over the last forty years have been reflected in the surrounding area. Nowadays, Borehamwood is a long, bleak strip of charity shops, orange-hued greasy spoons, tatty pawn shops and grim, boarded-up frontages.

In 2006, the town attempted to celebrate its unique connection to British cinema history with a series of semi-successful council-led displays. Along the roads are a series of metal information boards dedicated to the stars who worked at the studios.

Chock-a-block with history, they’re placed in large, unkept brick flower beds outside the pubs and 24-hour newsagents. When I was there, no one was paying them any attention at all, and most people looked at me with curious puzzlement when I took my camera out to photograph them.

On the High Street, large banners proclaiming “Made in Elstree” (although technically it should be “Made at Elstree” as the films were all made in Borehamwood) show stills from of the iconic movies made at the studios – hence, A Clockwork Orange’s Alex stares down menacingly at the old people shuffling past the pawnbrokers, Chewbacca growls at the traffic streaming over one of the countless traffic-slowing ramps, and Darth Vader flutters proudly over a branch of Nando’s.

At the railway station is a miniature walk of fame with one star commemorating Harrison Ford – the man who famously referred to the area as “Boring-wood.” A completely lackluster paving slab, it’s a fitting tribute.

In the Tesco itself, the only reminder of its former use is an aisle of Star Wars toys – situated not far from where the film which inspired them was created thirty years before.

The Elephant Man’s Hat

October 23, 2011

Arriving at Whitechapel – the single place in London still most closely associated with events which took place there over a century ago – it’s easy to feel you’ve stepped back in time. Arriving at the Underground station, you step out into a narrow railway shed made of wood and huge steel rivets. The only changes to the station since it opened in 1896 have been cosmetic ones; the structure still looks much the same as it did 115 years ago.

Directly opposite stands the London Hospital, which, like the station is much unchanged. It doesn’t take much – in my case, the sepia setting on my camera – to conjure up the East End of the 1880s (although it didn’t have the prefix ‘Royal’ until 1990, when it celebrated it’s 250th year.)

Even more remarkably, aside from the station and the hospital, the old shops next to the station remain untouched. While the occupants have changed countless times over the century, the fabric – the bricks and mortar – remain the same.

Looking back across the road from the London Hospital, the view is much the same as it would have been in the 1880s, when a Dorset-born surgeon named Frederick Treves (1853-1923) first came to work there as a Lecturer on Anatomy.

It was in this house – No. 259, Whitechapel Road, now the UKAY International Saree Centre, with an immigration service, mini cab office, travel agent and homeopathy clinic in the rooms above – where Treves first saw the man with whom his name would forever be associated.

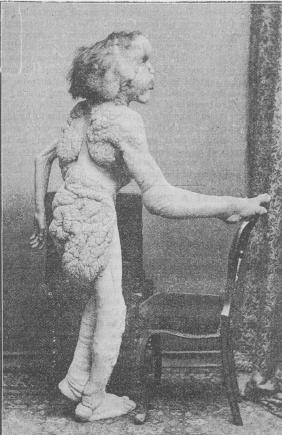

Joseph Merrick (1862-1890) – better known as The Elephant Man – is, along with Jack The Ripper, one of the men most closely associated with Whitechapel. And in a small museum attached to the hospital in the crypt of St Augustine in Newark Street are the sole handful of items associated with his short life which still exist.

None are more immediately evocative of his unique life than the hat and mask which he supposedly wore on the night he first visited the London Hospital in 1884.

Born in Leicester, “at the age of 5 years”, bony lumps and thick skin started to deformed and enlarge Merrick’s head, face, arms and legs. He was 11 when his mother died (by his own account, she doted on him) and just 12 when he left school and went to work “at Messrs. Freeman’s Cigar Manufacturers, and worked there about two years, but my right hand got too heavy for making cigars, so I had to leave them.”

As Merrick’s physical afflictions became progressively worse, work became harder to find (his father had once sent him out to sell products door to door, with predictable results) and he spent four years in the Leicester Union workhouse. Merrick recalled his time there with dread, and realised the only way to leave was to make a living. He realised that the deformities which prevented him from working were so extreme they could actually be used to his advantage. From the workhouse, he contacted two local showmen, music hall comic Sam Torr and music hall proprietor J. Ellis, with a plan to exhibit himself.

So thought I, I’ll get my living by being exhibited about the country. Knowing Mr. Sam Torr, Gladstone Vaults, Wharf Street, Leicester, went in for Novelties, I wrote to him, he came to see me, and soon arranged matters, recommending me to Mr. Ellis, Bee-hive Inn, Nottingham, from whom I received the greatest kindness and attention.

It was Torr, Ellis and a travelling showman ‘Little George’ Hitchcock who decided to present Merrick as ‘The Elephant Man, Half-a-Man and Half-an-Elephant’ as they toured around the East Midlands.

Realising he only had a limited regional circuit to display Merrick on before exhausting the audiences, Torr contacted Tom Norman (1860-1930), a London-based showman who specialised in presenting human oddities like the Skeleton Woman, The Balloon Headed Baby and Mademoiselle Electra (billed as “The Only Electric Lady — A Lady Born Full of Electricity”, she gave people an electric shock while shaking their hands.)

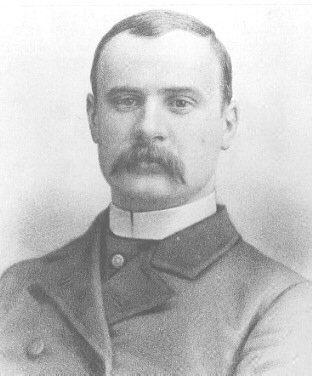

Tom Norman in his later successful career as an auctioneer

Tom Norman in his later successful career as an auctioneer

Norman specialised in penny gaffs – small rooms where sub-music hall, amateur entertainment turns could be seen for the entrance fee of a penny, which, by the 1880s, had largely fallen out of fashion. He took over Merrick’s management at the end of 1884 – although he was initially so shocked by Merrick’s appearance, he was reluctant to display him, thinking he looked too horrific to be a successful novelty. Thus Merrick came to be displayed in a vacant greengrocer’s at 123 Whitechapel Road (the road number has since been changed to 259.)

To accompany the display, a 3-page pamphlet – The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick – was printed (it is where the above quotes are taken from.) Alongside claiming that his features were the result of his mother being startled by an elephant while pregnant, he added that:

The measurement around my head is 36 inches, there is a large substance of flesh at the back as large as a breakfast cup, the other part in a manner of speaking is like hills and valleys, all lumped together, while the face is such a sight that no one could describe it. The right hand is almost the size and shape of an Elephant’s foreleg, measuring 12 inches round the wrist and 5 inches round one of the fingers; the other hand and arm is no larger than that of a girl ten years of age, although it is well proportioned. My feet and legs are covered with thick lumpy skin, also my body, like that of an Elephant, and almost the same colour, in fact, no one would believe until they saw it, that such a thing could exist.

While he might not have been the sole author of the pamphlet (at the very least, it bears a showman’s hand embellishing the truth), it is a common misconception that Merrick was a cruelly-treated victim of the showmen (which is how he was frequently portrayed later in popular culture, and, indeed, in the memoir of Treves.) Merrick was not just a willing partner in the enterprise, but the man who came up with the plan of exhibiting himself in the first place. He also shared in the profits and had been saving as much as he could in the hope of buying his own house.

In making my first appearance before the public, who have treated me well — in fact I may say I am as comfortable now as I was uncomfortable before.

But by 1884, the display of human oddities was becoming unpopular and the Elephant Man display at Whitechapel was shut by the police just a few weeks after it opened.

One of the visitors before it was closed was the 31-year-old Frederick Treves, who had been urged to visit by a younger surgeon friend.

He described first seeing Merrick in his 1922 memoirs The Elephant Man and Other Reminscences (published at the end of his life, they contain numerous errors which many put down to old age, including Treves stating that Merrick’s first name was ‘John’.)

The whole of the front of the shop, with the exception of the door, was hidden by a hanging sheet of canvas on which was the announcement that the Elephant Man was to be seen within and that the price of admission was twopence. Painted on the canvas in primitive colours was a life-size portrait of the Elephant Man. This very crude production depicted a frightful creature that could only have been possible in a nightmare. It was the figure of a man with the characteristics of an elephant. The transfiguration was not far advanced. There was still more of the man than of the beast. This fact—that it was still human—was the most repellent attribute of the creature. There was nothing about it of the pitiableness of the misshapened or the deformed, nothing of the grotesqueness of the freak, but merely the loathsome insinuation of a man being changed into an animal. Some palm trees in the background of the picture suggested a jungle and might have led the imaginative to assume that it was in this wild that the perverted object had roamed.

When I first became aware of this phenomenon the exhibition was closed, but a well-informed boy sought the proprietor in a public house and I was granted a private view on payment of a shilling. The shop was empty and grey with dust. Some old tins and a few shrivelled potatoes occupied a shelf and some vague vegetable refuse the window. The light in the place was dim, being obscured by the painted placard outside. The far end of the shop—where I expect the late proprietor sat at a desk—was cut off by a curtain or rather by a red tablecloth suspended from a cord by a few rings. The room was cold and dank, for it was the month of November. The year, I might say, was 1884. The showman pulled back the curtain and revealed a bent figure crouching on a stool and covered by a brown blanket. In front of it, on a tripod, was a large brick heated by a Bunsen burner. Over this the creature was huddled to warm itself. It never moved when the curtain was drawn back. Locked up in an empty shop and lit by the faint blue light of the gas jet, this hunched-up figure was the embodiment of loneliness. It might have been a captive in a cavern or a wizard watching for unholy manifestations in the ghostly flame. Outside the sun was shining and one could hear the footsteps of the passers-by, a tune whistled by a boy and the companionable hum of traffic in the road.

The showman—speaking as if to a dog—called out harshly: “Stand up!” The thing arose slowly and let the blanket that covered its head and back fall to the ground. There stood revealed the most disgusting specimen of humanity that I have ever seen. In the course of my profession I had come upon lamentable deformities of the face due to injury or disease, as well as mutilations and contortions of the body depending upon like causes; but at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed. He was naked to the waist, his -feet were bare, he wore a pair of threadbare trousers that had once belonged to some fat gentleman’s dress suit.

Treves arranged with Norman to examine Merrick at the hospital opposite the following day – but there was a problem.

I became at once conscious of a difficulty. The Elephant Man could not show himself in the streets. He would have been mobbed by the crowd and seized by the police. He was, in fact, as secluded from the world as the Man with the Iron Mask. He had, however, a disguise, although it was almost as startling as he was himself. It consisted of a long black cloak which reached to the ground. Whence the cloak had been obtained I cannot imagine. I had only seen such a garment on the stage wrapped about the figure of a Venetian bravo. The recluse was provided with a pair of bag-like slippers in which to hide his deformed feet. On his head was a cap of a kind that never before was seen. It was black like the cloak, had a wide peak, and the general outline of a yachting cap. As the circumference of Merrick’s head was that of a man’s waist, the size of this headgear may be imagined. From the attachment of the peak a grey flannel curtain hung in front of the face. In this mask was cut a wide horizontal slit through which the wearer could look out. This costume, worn by a bent man hobbling along with a stick, is probably the most remarkable and the most uncanny that has as yet been designed. I arranged that Merrick should cross the road in a cab, and to insure his immediate admission to the college I gave him my card.

In Norman’s autobiography, he stated Merrick went to the hospital “two or three” times, but then refused to go any more, feeling “like an animal in a cattle market.”

Following a disastrous tour of Brussels in 1886, where Merrick was abandoned by a promoter who ran off with his money and had to make his own way back to England, he found himself at Liverpool Street Station. Alone, the object of much unwanted curiosity, and fighting to make himself understood to the police, who’d dragged him away to stop the inquisitive crowds gathering around him, he handed over the card Treves had given him two years before.

Treves was contacted and the two men returned to the London Hospital, where Merrick was signed in – his age was given as 26, not 24 – and where he was eventually given permanent quarters. Unable to do much to help him, Treves displayed Merrick to the great and good – as much a showman as Sam Torr or Tom Norman.

Merrick entertained visitors much as did in the vacant greengrocer’s across the road, although now those who came to see him were aristocrats and did their best to hide their horror. He wrote them charming, courteous and childlike letters once they’d gone – the only surviving example known is on display in the museum.

Next to it is a cardboard church which Merrick made for the actress Madge Kendall (1848-1935), who was a prominent supporter and fundraiser for him, although it’s uncertain if they ever actually met (she did, however, send someone along to his room to teach him basket weaving after he’d expressed an interest in learning.)

The German printed paper models were frequent gifts from Merrick, who was able to write and work with his largely undeformed left arm, but again, this is the only one known to survive.

Merrick died in his sleep in his basement room in the East Wing overlooking Bedford Square on the afternoon of 11 April 1890, the result of a dislocated neck caused by the weight of his head. Due to spinal deformities, he had to sleep on his knees with his head forward; on the night he died, he had lain down – Treves wrote in his memoirs that Joseph had always wanted to sleep “like other people.” He was 27.

The coroner at his inquest was Wynne Edwin Baxter, who had come to prominence during the notorious Jack the Ripper murders of 1888. Nothing belonging to Baxter is in the museum, but the gloves of pathologist Sir Thomas Openshaw (1856-1929), who identified the piece of kidney sent by the Ripper to Inspector Lusk, are on display, along with his collection of Masonic medals.

The Elephant Man and the Ripper represented the two extremes of humanity in Whitechapel in the 1880s. Both became world famous under their pseudonyms, both are immediately associated with Whitechapel, and both form part of the underbelly of poverty and misfortune in London during the 1880s.

But while Merrick was an ordinary, decent man with a face that made him seem inhuman, the Ripper was his mirror image; a man without a face who came to represent inhumanity. That both should have lived out their very different lives in the same place at the same time is one of London’s strangest stories.

Merrick’s skeleton is kept by the Royal College of Surgeons, but it has never been on public display.

The Royal London Hospital Museum is in the former crypt of St Philip’s Church, Newark Street, Whitechapel, London, E1 2AA. Nearest tube: Whitechapel.

Note: My thanks to Mae for correcting a couple of errors in this piece. Her fascinating site dedicated to Merrick is at http://www.josephcareymerrick.com/

Widely regarded as one of the truly essential London films, the 1968 documentary The London Nobody Knows was based on a bestselling gazetteer-cum-memoir written by Geoffrey Fletcher, an illustrator and Daily Telegraph journalist.

Directed by Norman Cohen (best known for later helming the long-running 1970s Confessions Of…sex comedy series), the 46-minute film features a melancholy James Mason leading an hour-long tour through the seamier streets of Swinging London, eschewing tourist sites for meths drinkers, shoeless children and bleak Victorian tenements.

Forty years after it was made, and after a decade of being the BFI’s single most requested title, The London Nobody Knows was finally released on DVD in 2008.

While Fletcher was billed as the film’s writer, the documentary was actually scripted by Brian Comport, who was only given a credit for “additional material” on commercial grounds. Now in his seventies and living in “sunny Brixton”, the dapper Comport is the only person involved in the film who has lived to see it acknowledged as a classic.

This is an interview I conducted with him, first broadcast on my old film show on Xfm.

How did The London Nobody Knows come to be made?

Norman Cohen, who produced and directed The London That Nobody Knows, had done four shorts for the Boulting Brothers and, as part of the deal he was on, had been offered a fifteen minute documentary. In 1966, he’d worked with James Mason on a film called The Blue Max as sound editor, had mentioned that he was thinking of doing this book as a documentary and Mason said “I’d love to do it.” That promptly raised money for another half hour. So Norman called me in. I was living on Bankside and I took him around, and he said “Right, go for it. Write me all this material.” So I did. He said “Look, the book on which it’s based is basically a point of departure, but the title The London Nobody Knows has got great marquee value, we’re sticking with that title because legally we have to, and as such, I’m going to have to acknowledge the author of the book, Geoffrey Fletcher.”

How much was Geoffrey Fletcher involved with the film?

Well, he wrote the book. He was a graphic artist, very good one, for the Daily Telegraph and exhibitions, and a bit of a history buff about London, a bit like Peter Ackroyd. He would have been, I suppose, a bit erudite for Norman when it came to the film. So I took it from there.

What was Fletcher like?

I never met the man. I read the book but I never met the man at all. He certainly knew his stuff as an artist and historian, though.

What was the reaction when the film was first released?

There was a very strange reaction to it. People didn’t know what to expect, frankly. Some people described it as ‘quirky’; some people described it as ‘quaint.’ Recently, someone called it an early fly-on-the-wall documentary, imitated since by television. At the time though, it was a very “Comme Ci, Comme Ça” reception – although we thought it might be a bit of a sleeper, and so it’s proved to be.

What’s do you put its enduring appeal down to?

I would say it was the humanity. Norman was a lovely man, had a great sense of mischief and he looked for characters – we filmed the kids, we filmed the olds and we filmed the down-and-outs. We took our lives in our hands in the really itchy part, where we had this evil-minded absolute raving animal of an alcoholic – poor devil – and we had a camera either side of him, knowing we’d have to be ready to drop them and just run if necessary.

Was the writing done during the filming process?

No, no, I’d written the material but when you get someone like James Mason, obviously if he wants to extemporise, that’s entirely down to him! Norman would have been a fool to have it any other way. So, no, the script was written before.

So there’s no treasure trove of unused material that one day will come to light?

I doubt it. There’s an out-cut that I don’t think will ever see the light of day, as I don’t think it was printed off. We were on Tower Hill with the escapologist.

Mason was talking on a prompt from my script, and he happened to mention in passing about being a Cockney, which I am – born in the sound of Bow Bells, in Cheapside. And this bloke breezed in, camera running, “’Ere, Mr. Mason, now, let me correct yew on that small matter. The Bow in question is ver Bow down in Poplar, right? It’s not anywhere else.” Mason was flummoxed – he was so urbane, gentlemanly, and polite – and Norman leant over to the cameraman and just whispered “Let it run! Just let it run!” But then he had cold feet and we canned it, so I don’t think it saw the light of day in any physical sense, and it’s not likely to ever turn up.

It’s astonishing watching someone the stature of James Mason walking through the rough streets of London and the commotion it causes.

Oh, it did! He had a driver and I would share the car occasionally, and he was standing with my partner at the time, when a little girl came up to her and said “’Ere, if that’s Mr. Mason, are you Mia Farrow?” They assumed anyone near him was famous too.

Considering the muted critical reception, I presume there were no plans for a follow-up, despite Fletcher writing more London titles.

Well, Norman went on to do ‘Til Death Us Do Part and Dad’s Army, and I did two or three more movies, and so that was it. It was an early point in his career and in mine. I was very fond of all the films I later made, but I was always particularly fond of London. Norman was a great mate, and it’s very moving, a lot of it.

Are you surprised by the level of acclaim it’s enjoying after forty years?

I must say I am, but I think it a thoroughly decent picture, and I’m sorry that Norman isn’t here to enjoy the accolades. I feel like a broom in a broom cupboard, that someone’s wondered what it’s doing in there, has brought it out and finally put it to good use. When I saw the film again the other day, I was very pleased with it. And that’s a very nice feeling.

The London Nobody Knows is available as an Optimum Classic DVD as part of a double-bill with Les Bicyclettes de Belsize, and is available here and here (I’m only making life easier if you want a copy – I don’t have any association with these vendors.)

The documentary is also up on YouTube, but it probably shouldn’t be for sorts of copyright issues. The quality isn’t a patch on the DVD.