City of London Pubs (1973): Forty Years On – Part 5

November 25, 2014

Please note: I’m jumping ahead here, but the long-delayed Part 1 will follow in the next week!

This is the fifth part of my walk following the route of City of London Pubs: A Practical and Historical Guide by Timothy M. Richards and James Stevens Curl.

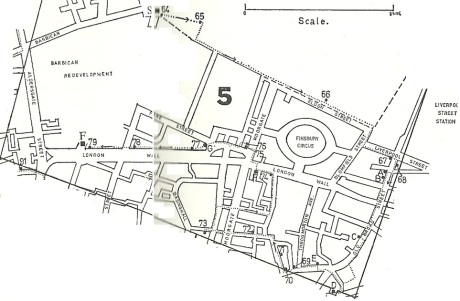

AREA 5: THE BARBICAN, MOORGATE AND FINSBURY CIRCUS

For Richards and Curl, Area 5 was “our largest tour, topographically speaking” – but today, it’s the area which drives home just how much the City has changed in the last forty years.

Once, this area was the heart of the City’s brewing industry. On Chiswell Street stood the Whitbread Brewery, founded by Samuel Whitbread in 1750 as the country’s first purpose-built mass-production brewery. On the wall outside, a stone plaque records a 1787 visit by George III and Queen Charlotte – their visit was commemorated with two rooms used for storing beer named in their honour.

Once, this area was the heart of the City’s brewing industry. On Chiswell Street stood the Whitbread Brewery, founded by Samuel Whitbread in 1750 as the country’s first purpose-built mass-production brewery. On the wall outside, a stone plaque records a 1787 visit by George III and Queen Charlotte – their visit was commemorated with two rooms used for storing beer named in their honour.

The brewery is no longer operating, but it was still a working brewery when Richards and Curl were writing in 1973 – they wrote that Whitbread’s “is now the sole survivor” of the City breweries, which had once been 40 strong – but it closed three years later in 1976.

The real damage to the City’s historic pubs started at this point, but it was really during the 1990s and early 2000s that the trade took a hammering it can never recover from. Bigger profits were to be found outside the pubs: in the value of the land and in other, more profitable, businesses.

The company used the Brewery as their headquarters until 2001, when they decided to wash their hands of the pub trade after two-and-a-half centuries. Their website proudly states:

In 2001 we became the company we are today. We sold our breweries [in 2000] and left the pub and bar business [selling off their pubs in 2001], refocusing on the growth areas of hotels and restaurants. Our reinvention as the UK’s leading hospitality business naturally coincided with the ending of this country’s brewing and pub-owning tradition, started by Samuel Whitbread over 250 years earlier.

Since 1995, Whitbread have owned the Costa Coffee chain, and this, along with Premier Inn and Brewers Fayre restaurants, has been the main focus of their business ever since.

The Whitbread Brewery was sold to an investment firm in 2005 and is now The Brewery, “a premier corporate venue” and “a leading conference space.”

I’ve been there for an awards-do and it’s very pleasant, but I can’t shake the feeling that are lots of other similar corporate venues dotted around the neighbourhood, and it would be far more special if it had remained a working brewery. Of course, that comes down to profit, and if that’s not there, what can you do?

The fate of the Whitbread Brewery was the same as many of the pubs which Richard and Curl visited in 1973, and their writing makes it clear they were largely unaware of the extent of the creeping destruction which was just around the corner.

This walk is close to a tipping point in my survey – this is the first walk where the number of lost pubs far exceed the number which have survived. Five pubs that Richards and Curl visited in 1973 are still here; but ten have gone. The City has lost so many pubs by this point in my survey that nearly half of the pubs which Richards and Curl visited in 1973 have disappeared.

The huge office blocks which now dominate the area have also entirely changed the area’s topography. What used to be a street with numbers neatly along its length has often been replaced with vast glass atriums with company names etched onto the glass, and entire sections of the roads have been replaced by single buildings. Occasionally, this has made it hard to pinpoint the exact locations of lost pubs.

Additionally, there seems to be a concerted effort to hide road names when office blocks have taken over. Many street signs (some of them very old signs themselves) are placed high above the level of the street, often on one side only and at angles that make it almost impossible to see. Why this should be, I have no idea.

No.64 – THE KING’S HEAD, 49 Chiswell Street, EC1

Noting that Chiswell “is probably a corruption of the brewery’s ‘choice well’”, Richards and Curl call The King’s Head the “first of the Whitbread brewery taps…The interconnected saloon and public bars are always bustling, patronised mainly by brewery workers and men from the Barbican site. The small saloon lounge inevitably fills up in no time at all…A large mural depicting the brewery in olden days graces one wall.”

The pub has now gone, replaced with a smart bistro called The Chiswell Street Dining Rooms, which stretches four shop-fronts along the road. There is a bar inside, but it is certainly not a pub – the menu outside sounds delicious, but anywhere offering “prune and Earl Grey tea puree” on the side of a dish is definitely a restaurant.

As is often the case when I wander around the City with a camera, a gentleman who worked at the Dining Rooms came over to ask me what I was doing when I was photographing the building. As soon as I’d said “I do a blog”, he immediately relaxed and told me to pop in for a drink if I fancied. I can tell you that isn’t the usual response I get – some people have asked me for “ID proving you’re a historian”, which I don’t think actually exists – so thanks to him. I didn’t have the drink, but I appreciated the gesture.

No. 65 – THE ST PAUL’S TAVERN, 56 Chiswell Street, EC1

At the junction with Silk Street, on the other side of the Brewery’s entrance from the King’s Head, formerly stood the St Paul’s Tavern, a “popular pub” where “space…is always at a premium.” It has now been renamed the Jugged Hare, and while more obviously a pub than the Chiswell Street Dining Rooms, it is not what anyone could term a boozer.

Looking at the menu outside, I noticed the bottom of the menu has the same details as the one outside the Chiswell Street Dining Rooms, noting it was owned by ‘the ETM Group’. Slightly lower priced than its sister business, it was similarly filled with suited City types and certainly isn’t the sort of place you’d wander into wearing jeans and carrying a copy of the Racing Post.

The problem here is that if it looks what a pub traditionally looks like, it has a bar and it serves a decent pint of beer, is it still a pub? I’ve thought about this a lot for the purposes of this survey, and I’ve come to the conclusion that it isn’t necessarily.

There are certain things which are integral to pubs that go beyond that – could you pop in for a swift half with two mates on the way to a gig? Could you nip inside to keep out of the rain, and nurse a half for the best part of an hour? Would you go there on a Sunday morning to read the papers? Is the bar the focus of the building as opposed to the restaurant? The answer to all those questions is no.

It might seem as if I’m splitting hairs, but I think the main purpose of a pub has to be to primarily serve alcohol to people in a social environment. If the main focus is on food, and not on serving beer, then it’s a restaurant. So while the Jugged Hare looked very nice, it’s not any longer what I think can be termed a pub.

No. 66 – THE RED LION, 1 Eldon Street, EC2

As Richards and Curl state, the Red Lion (like the two previous businesses) is ever so slightly outside the boundary of the City, but aside from saying its busy, they spend little time on the overall look. Perhaps it’s due to the glass cliffs which now tower above it, but the Red Lion looked terrifically inviting from the outside, and more so when I looked through the door.

Run by Taylor Walker, it’s a snug, dark wooden room which was full of pre-Christmas afternoon cheer.

No. 67 – THE RAILWAY TAVERN, 15 Liverpool Street, EC2

“Standing as it does opposite Broad Street and Liverpool Street Stations, The Railway is an obvious place to down a quick pint while waiting for a train. More trains have been missed for this reason than all others put together we suspect. The second of Whitbread’s ‘theme’ houses (owned jointly with Bass), this one is a real Mecca for railway enthusiasts. The large, once stately, lounge houses numerous prints, photographs, and notices concerning railway history. Two models stand out in particular – an LNER Coronation Coach and the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway’s ‘Jenny Lind.’”

While these pieces of railway memorabilia have long gone, The Railway remains, now subdivided into bars: the main one, an upstairs bar and dining room called The Engine Room, and one smaller round the back, named the Citybar – a name that immediately makes me think of 1980s Yuppiedom (perhaps also because it comes complete with a stained glass window reading ‘Wine Bar’ above.)

Not withstanding the handsome sub-classical exterior, the inside is a bit gloomy, with the darkness punctured by the flash of fruit machines, Sky Sports on the flatscreens and an Atom-bomb-bright board on showing rotating adverts for Now That’s What I Call Music compilations and local estate agents. It hadn’t put many people off, as it was busy inside.

Next door, the pub’s proximity to the railway was spelled out: Crossrail’s redevelopments are taking place, but it’s a relief to see the pub incorporated into the developer’s idealised vision of the future of the area.

No. 68 – PATMAC’S RAILWAY BUFFET, 73 Old Broad Street, EC2

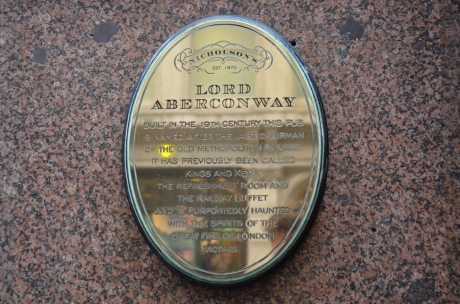

“Essentially, as its name suggests,” wrote Richards and Curl in 1973, “Patmac’s (Patrick & Macgregor) is a buffet bar for Liverpool Street Underground Station…It is interesting to note that Liverpool Street should have a buffet bar here, as it is now the only tube station apart from Sloane Square possessing a bar actually on the platform.” While the Liverpool Street tube bar is long gone, Patmac’s is still operating, although now it goes by the much preferable name The Lord Aberconway.

A lovely Victorian bar – probably the most handsome interior of all the pubs on this walk – it’s run by Nicholson’s, who are one of the few brewers to proudly retell the history of their pubs on handsome plaques outside (I award extra bonus points for mentioning ghosts and/or the plague). The name change – Lord Aberconway was the last chairman of the Old Metropolitan Railway, which amalgamated with other lines in 1933 to form the Underground as we know it today – is relatively recent, but the pub itself (despite the frequent name-changes) looks as if it has been largely unchanged for years.

Letter E – THROGMORTON BAR, 27 Throgmorton Street, EC2

No.69 – THE BODEGA BAR, 30 Throgmorton Street, EC2

Throgmorton Street was, for many years, dominated by the bars along it, serving the workers in the nearby Stock Exchange.

During the 1970s, the Throgmorton Bar was “a darkly-panelled bar in vaguely seventeenth-century style, with ‘period’ plaster ceiling in the Jacobean manner…the showpiece of this bar is, however, undoubtedly the mosaic-clad stairwell that leas down to the basement. The stairs winds it way round an elegant wrought-iron cage containing the lift shaft. The mosaics are richly colourd, with classical Pompeian friezes and much use of gold.” Its near-neighbour, the Bodega Bar, was “a remarkably long, narrow bar…based on a styling vaguely art nouveau. The walls are subdivided by pilasters of alabaster and marble, and the plaster ceiling is enriched with sub-Art Nouveau and Rococo motifs.”

While not doubting Richards and Curl’s appreciation of these places (it sounds a little like the decor of these bars might not be to modern tastes), all have since disappeared over the years as whatever redevelopment is happening in Throgmorton Street continues to not happen.

Unlike most City developments, there are no signs promoting any new developments ‘coming soon’, even though it looks as if the road is definitely being prepared for redevelopment.

Throgmorton’s closed in 2008, the long-running Throgmorton’s restaurant (responsible for the elaborate metalwork along the road, most of it dating from the time the restaurant was owned by the Lyon’s chain) in 2013, and a pub not mentioned in City of London Pubs called The Arbitager was the last to be operating in the main portion of the road.

I went in once a few years back, and it was simply unique – with the racing on, and unpainted walls, it looked more like a Dickensian hole-in-the-wall gin shop than a pub. No less exciting for that. Now it too has gone the way of all the rest.

No.70 – MOORE’S BAR, 34a Throgmorton Street, EC2

At the lower end of Throgmorton Street, where Moore’s Bar once stood – “below pavement level, the subterranean bars are loaded with Victoriana, especially mirror advertisements of the late nineteenth century, stuffed fish and other period bric-a-brac” – the buildings have all been demolished and are awaiting office blocks.

No.71 – BIRCH’S, Angel Court, Ec2

“Chiefly a wine house,” note Richards and Curl, “the shop front, with its three semi-circular leaded windows, is a passable replica of part of the eighteenth-century original [Birch’s wine shop in Cornhill]…the interior is small and intimate, with a board floor. There is a splendid open screen of vaguely Gothick style separating the front bar from the rear alcove containing tables – a most charming feature.” All these features have now gone, along with the historic name – the only business along the street in a building similar to the one Richards and Curl described is the Mint Leaf Lounge, a huge open plan bar which looks a lot of the lobby of an expensive hotel, all honey lighting and strange human-shaped silver statues.

No. 72 – THE BUTLER’S HEAD, 11 Telegraph Street, EC2

New in 1973 – “another undistinguished addition to the City” – this pub has since been replaced by a later office block with a pub underneath called The Telegraph.

By far the largest of all the pubs I saw on this walk – honestly, you could take the tables and chairs out and play a football match inside – The Telegraph is run by Fullers. It’s newness makes it look like a branch of the Slug and Lettuce and it lacks charm – but I suppose its main purpose is to cater efficiently for large numbers of workers on a weeknight rather than act as a cosy local.

Due to the fact that neither Richards nor Curl would recognise this site in the slightest, and the fact the name of the pub which used to be on this site has been lost, I’m counting this as a new pub which has opened on the site of an old one which closed.

No.73 – YE OLDE DOCTOR BUTLER’S HEAD, Masons Avenue, EC3

Set in a beautiful avenue of half-timbered, narrow old houses, this pub was named after Dr William Butler, the Court Physician to King James I. Famous for inventing a popular medicinal ale, the pub which takes his name is old, but was significantly remodelled in the 1920s.

Largely preserved since then, when I visited it had been renamed The Movember Arms to promote the excellent men’s health charity Movember. Hopefully this renaming is just for the month of November – I must admit, it’s so professionally done, there’s a part of me that’s ever so slightly worried it won’t be changing back. Thankfully the barrels hint the name isn’t here to stay…

No. 74 – THE STIRLING CASTLE, 50 London Wall, EC2

“A late nineteenth-century pub with a strongly designed exterior,” wrote Richards and Curl, “somewhat spoiled by the loss of its original glass.” More than the glass has gone now – the entire pub and surrounding buildings have been demolished and replaced with the ubiquitous office block with shop units underneath.

The lack of numbering on this faceless block means its hard to tell exactly where the pub would have been – it looks to be where LA Fitness is. A couple of original metal plaques have been salvaged by the developers and pinned to the front of the modern building like the scalps of defeated enemies – one, which reads ‘SCS 1886’ seems to fit the date of the old pub given by Richards and Curl, with the ‘SCS’ perhaps incorporating the initials of ‘Stirling Castle.’ This is just a guess – if anyone knows any better, please let me know!

No. 75 – THE GLOBE, 83 Moorgate, EC2

“The Globe is one of those pubs that no one knows by its real name; it is universally known as The 199.” While I don’t think anyone knows the pub as The 199 these days, the Globe is still standing, huddled together at the edge of a small group of old buildings kept standing as all the surrounding ones have been knocked down to build offices.

Huddled together amidst the skyscrapers, the Globe is a hardy survivor –“it was mentioned in 1734 in records of the Clockmaker’s Company, and we know that John Wilkes ‘dined at Globe near Moorgate’ in 1770.” Nowadays there don’t seem to be many radicals coming through the doors, only City workers having a couple of pints before heading to Moorgate station just a few wobbly steps away.

No. 76 – THE MOORGATE, 85 Moorgate, EC2

Located directly next door to the Globe in 1973, the inn was once known as The Swan & Hoop, and it was here that the poet John Keats was born in 1795 (his father managed the livery stables at the inn, although whether Keats was truly born here or at his parent’s unidentified nearby house is lost in the mists of time.)

The Moorgate is no longer running, having been swallowed by its neighbour at some point and renamed ‘Keats at the Globe’, although I’m not entirely certain if they are actually connected as a whole. The house bears a plaque commemorating Keats’ birth and the house – not original to the time Keats was born and now looking really tired –probably has its famous connection to thank for escaping the redevelopment which has started one door down. As the pub is now just an overspill of The Globe, I am counting it as lost.

No.77 – THE PLOUGH, St Alphage Highwalk, London Wall, EC2

No. 78 – THE PODIUM, St Alphage Highwalk, London Wall, EC2

No. 79 – THE BARBICAN, St Alphage Highwalk, London Wall, EC2

These pubs were “three new highwalk public houses” located in the Barbican development (which, at the time of Richards and Curl’s 1973 book wouldn’t be completely finished for another three years.) All were situated on the same Highwalk (the name given to the passageways in the complex which were high above street level), all appeared during the early 1970s, and all shut during the 2000s, ahead of a redevelopment of the fringe on which they were situated.

Along with the pubs, St Alphage Highwalk has itself been terminated.

It currently leads nowhere, blocked off at one end and cut off at the other, as ‘London Wall Place’ (another office) is erected on the site where the pubs once stood, alongside a universally unloved late-1950s skyscraper named St Alphage House. The small parade of shops on the site always underperformed and the units had been empty for a number of years. After the recession stalled a number of projects, the parade and St Alphage House were finally demolished earlier this year.

There are still two places to get a drink by the Barbican, however: situated on Moorfields Highwalk is the City Boot…

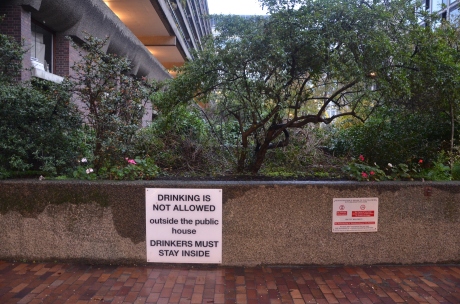

…while close by the Church is Wood Street, a restaurant which also serves drinks. It has a pub sign outside and a snooker table (although with red baize, which I have problems with), so I’m happy to count it as a pub. It was formerly known as the Crowders Well before its current incarnation.

It also has a sign outside that pleased me greatly. “Drinking is not allowed outside the pub. Drinkers must stay inside.”

That’s what people who use pubs should always be. Not customers, not guests, not patrons.

Drinkers.

Two quick notes

In this walk, Richards and Curl also included a number of wine bars (or as they had it, places that were “not a pub in the true sense of the word, but included as a drinking establishment”), which they chose to letter from A to F, rather than number like pubs. All but one of them – Gow’s Oyster Bar on Old Broad Street, which looked like a great place to go at Christmas and was fit to bursting with bald businessmen enjoying a late seafood lunch – have long gone, as, unlike pubs, when the owner left, the business didn’t continue. As such, I have left them off this survey, as I have done with new wine bar/club places, such as Babble City (which looks as if it was specifically designed to scare off anyone over 30) on Wormwood Street.

Additionally, a few proper new pubs have appeared in the forty years since City of London Pubs was written. At no. 26 Throgmorton Street is the Phoenix, a large cavern of a place with dark wood interior…

…and on Wormwood Street sits the King’s Arms, a Taylor Walker pub situated underneath a tower block which must have sprung up in the years following Richards and Curl’s book.

THE TALLY SO FAR:

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs still open: 32 (4 renamed)

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs now closed: 31

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs which had closed and are now open: 1

Pubs opened since 1973’s City of London Pubs: 6

The Men Who Wrote Shakespeare

May 4, 2011

Whether one believes a barely-educated glove-maker’s son from Stratford-Upon-Avon could produce the greatest single body of literature in the history of the world or not (and if you want to find yourself unsure, John Mitchell’s excellent Who Wrote Shakespeare? (1996) will give you plenty of conspiracy food for thought), one fact is unassailable: the man known as Shakespeare didn’t write the plays which we can pick up and read today.

That’s not to say the words weren’t his – but if William Shakespeare ever physically wrote any of those words down, nothing has survived. Instead, the plays we know today as ‘Shakespeare plays’ are the work of two men who have been largely forgotten: the actors John Heminge and Henry Condell.

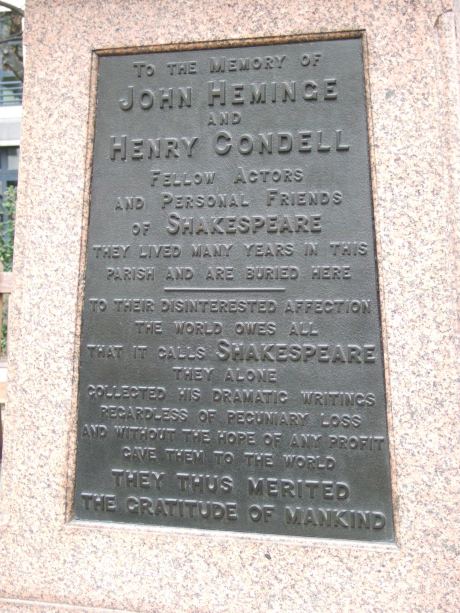

I say ‘largely forgotten’, but in the City churchyard of St Mary Aldermanbury, EC2, is a memorial dedicated to them both.

While the bust of Shakespeare sits proudly on top of the memorial, the plaques on the main body are dedicated to Condell and Heminge.

The text reads:

To the memory of JOHN HEMINGE and HENRY CONDELL, fellow actors and personal friends of SHAKESPEARE. They lived many years in this parish and are buried here.

To their disinterested affection the world owes all that it calls SHAKESPEARE. They alone collected his dramatic writings, regardless of pecuniary loss and without the hope of any profit, gave them to the world.

THEY THUS MERITED THE GRATITUDE OF MANKIND.

The two were Shakespeare’s co-partners at the Globe theatre in Southwark, and on his death in 1616

from the accumulated [plays] there of thirty five years, with great labour selected them. No men then living were so competent having acted with him in them for many years, and well knowing his manuscript, they were published in 1623 in Folio, thus giving away their private rights therein. What they did was priceless, for the whole of his manuscripts with almost all those of the dramas of the period have perished.

There’s no question of an authorship controversy here. The two men state unequivocably that Shakespeare was the author of the plays at a time when many of his contemporaries were still alive. It is one of the strongest refutations ofthe idea Shakespeare was not their author.

If it wasn’t for Heminge and Condell, the works of Shakespeare could have been lost to the world forever. They were the fine thread between us having the work of the world’s greatest writer and it being lost entirely.

How different the world would be if they hadn’t sat down one day, with a pile of dusty papers and half-remembered passages they’d performed a decade before, and thought, “Well, maybe we should try and get the lot of them written down for posterity.” It starts to make me feel ill at the thought of the great works that have been lost forever simply because there was no Heminge or Condell around to save it.

Everytime someone performs a Shakespeare play, there should be a round of applause at the start for the men who ensured that Shakespeare’s words survived.

The Church of St Mary Aldermanbury no longer stands, but was first mentioned in 1181 and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren following the Great Fire of London in 1666. Bombed during the Second World War, the stones were removed in 1966, shipped to America, and the church was rebuilt in the grounds of Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. It was erected as a memorial to Winston Churchill, who had given his famous ‘Iron Curtain’ speech in the Westminster College gymnasium in 1946.