Angels, Lyons and the World’s Most Popular Board Game

January 23, 2013

The thing I love most about London’s history is how it often pops up in the most mundane of settings.

Just after Christmas, I set out to close a Co-Op bank account that I’ve not used for years. The nearest branch to me is in Islington, just opposite Angel tube station. Look, I’m aware neither of those are the most dynamic opening sentences, but bear with me. I did say the setting was going to be mundane.

It’s one of the more perplexing names in the tube network – why did they go for Angel? Why not Islington,or Upper Street, or something a bit more geographically helpful?

The answer is that it’s one of five tube stations named after a pub (the others are Elephant & Castle, Manor House, Royal Oak and Swiss Cottage) and when the Angel tube station opened in 1901, the Angel Inn was still thriving on the corner of the High Street – much as it had done since the fifteenth century.

But within twenty years of the tube station taking its name, the Angel Inn was closed. Today, the tube station is the only reminder that it was ever there.

According to Henry C. Shelley’s The Inns and Taverns of Old London (1909):

The Angel dates back to before 1665, for in that year of plague in London a citizen broke out of his house in the city and sought refuge here. He was refused admission, but was taken in at another inn and found dead in the morning. In the seventeenth century and later, as old pictures testify, the inn presented the usual features of a large old country hostelry. As such the courtyard is depicted by Hogarth in his print of the Stage Coach. Its career has been uneventful in the main.

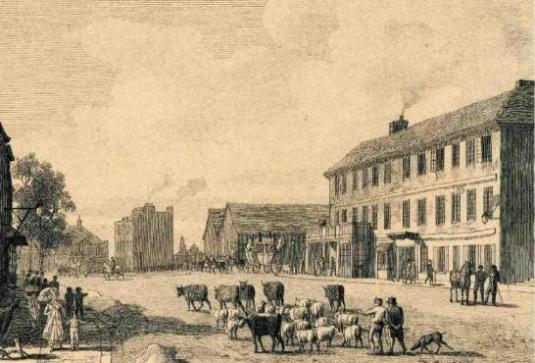

Its career may have been largely uneventful, but the inn survived for generations and the galleried interior was immortalised by some of the most celebrated English artists of the day: not just Hogarth in The Stage Coach: Country Inn Yard (1747)…

…but later by Thomas Rowlandson (in Outside the Angel Inn, Islington)…

…and Charles Dickens, who called the Angel “the place London begins in earnest” in Oliver Twist.

Despite an 1819 rebuild as the area rapidly transformed from a rural to an urban one (some of its land was sold off to realise some healthy profits), the Angel Inn was eventually demolished in the dying years of the nineteenth century.

But the Truman, Hanbury, Buxton and Co brewery had no intention of closing the pub down – instead they were going to make The Angel more popular than ever before.

But the Truman, Hanbury, Buxton and Co brewery had no intention of closing the pub down – instead they were going to make The Angel more popular than ever before.

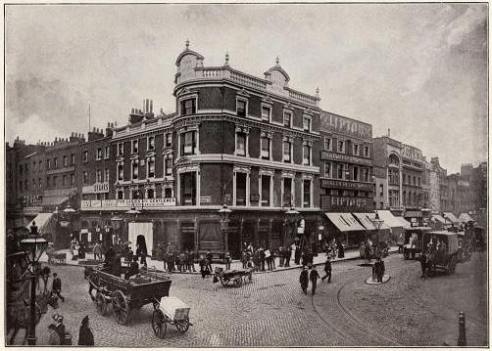

In 1899, they rebuilt the old pub as an ornate, six-storey, terracotta-brick building which still stands today.

Renamed the Angel Hotel, the new building was intended to do justice to what the brewers described (with some marketing hyperbole) as “the widest-known hostelry in the world.” The ground floor was faced in polished Norwegian granite; carved stone cherubs look out from the higher eaves; a mahogany and green-marble staircase led from the bar to a smoking room upstairs; and crowning the entire heap sat a grand baroque cupola, which quickly became one of Islington’s landmarks.

But within twenty years, the Angel Hotel had closed – its grand, high-Victorian design swiftly looked out of date and unfashionable, and the building’s three-hundred year history as an inn came to an end in 1921. The brewery sold the building to the Lyons catering empire, most famous for their vast Corner House restaurants which dominated the West End in the post-war period.

Staffed by waitresses affectionately known as ‘nippies’, the Corner Houses were more like department stores than tearooms, with several restaurants, numerous floors and hundreds of staff. In the 1950s, the company could boast it was serving over a hundred million meals a year to the British public.

The Angel Cafe Restaurant was opened in February 1922 as a grand, two-storey restaurant – large, but not on the same scale as the massive centrally located Corner Houses. The novelist Arnold Bennett came for lunch in 1924, and wrote that he preferred the “brightness and space” of the Lyons house to “the old Angel’s dark stuffiness.”

It lasted until 1959, when the Lyons company sold the building to the Council. Road widening schemes had been constantly mooted throughout the century (one estimate claims the corner was subject to seventy individual road-widening schemes from 1890 until the 1970s) and with a compulsory purchase order about to come into effect on the building, Lyons sold the site to the council a few years before they would have had to.

The decision was made easier for the company due to the increasing cost in the upkeep of the now shabby building – a slow and steady decline in Lyon’s trade from the end of the Second World War onwards meant the company were already feeling the downturn in fortunes which would see them go under in the 1970s.

The building was leased to the University of London’s Geology department until 1968, and then spent a number of years empty until the council finally abandoned their road widening schemes. Having escaped demolition by the skin of its teeth, it is now listed and has been fitted for bank use since 1979.

And that’s where we come in, with me popping in to close a bank account in the Co-Op, who occupy it today.

And that’s when I noticed this inside the front entrance.

The huge gold plaque commemorates the day in 1925 when the building was still the Angel Cafe Restaurant, and Victor Watson stopped by for lunch.

Watson was the managing director of Waddingtons, a firm of printers from Leeds who in the 1930s had started to branch out into card and board games. In 1935, the company sent a game they’d devised called Lexicon to the Parker Brothers in America, hoping they might agree to produce it in the States. In return, the Parker Brothers sent them one of their board games that had not yet gone into production: Monopoly.

Following a weekend of play, Victor’s son Norman urged his father to quickly snap up the rights, and three days after Victor had received the game, Waddingtons obtained the licence to produce and market Monopoly outside of the United States.

Watson felt that for the game to be a success in the United Kingdom, the American locations on the board needed to be replaced, so he and his secretary, Marjory Phillips, travelled to London for a day to work out which street names they would put on the board.

By all accounts, Victor and Marjory’s single day in London was a hectic one – Victor later admitted he’d slipped up by putting ‘Marlborough Street’ on the board when it should have been Great Marlborough Street – but in a short period of time, they managed to pick a broadly accurate selection of roads to represent the varying values across the board.

One of the only known facts about their day out (which would turn out to be a very lucrative one for the Waddington’s company) was that Victor and Marjory sat in the Angel Cafe Restaurant in the afternoon and reviewed their work.

And whether it was to celebrate completing their job, or just because he liked the name, Victor decided to include ‘The Angel, Islington’ on the board. Unlike all the other property squares, it’s the only one which isn’t a street, but a specific building.

You can find this plaque, unveiled in 2003 by Victor’s grandson (who is also called Victor and is also the managing director of Waddingtons), just as you walk into the Co-Op bank at 1 High Street, Islington.

A couple of doors away, there’s a Wetherspoon’s which has taken the name The Angel, but don’t be fooled. This Angel can only trace its history back to 1998.

The Shakespeare’s Head

July 13, 2011

At 29 Great Marlborough Street, W1 (but most often approached by Carnaby Street, where it’s situated on a corner where the street meets Fouberts Place) stands The Shakespeare’s Head.

The sign outside the pub claims the inn was established on the site in 1735 and was named after the owners, Thomas and John Shakespeare, who claimed to be distant relations of their famous namesake. Nothing of the original establishment remains – the building which stands today is late nineteenth-century (albeit in a Tudor style) – and there are serious doubts over whether it has any connection even with Shakespeare’s descendants. After all, The Shakespeare’s Head is a fairly common pub name in London – others can be found in Holborn, the City, Kingsway, Finsbury and Forest Hill.

It’s likely Thomas and John Shakespeare form part of a colourful story about the pub’s origins, and one which has been stated with increasing conviction over the years. The presence of the claim on a nicely-painted board outside the pub certainly helps attract the passing tourists ambling down Carnaby Street, but it doesn’t make the story any more likely to be true.

What the pub does have, however, is one of London’s most charming Shakespeare statues.

There are others dotted around the capital – Leicester Square, Westminster Abbey, on the front of City of London school, a bust in the churchyard of St Mary Aldermanbury – but none with the playfulness of the one which peers out from a window-like recess of the pub.

There’s just something perfectly realised about the position of the body. While the face is cold and fixed, the stance of the body really conveys him casually examining the crowds below – a fixed moment where the greatest playright of all time is half-looking for inspiration in the throng that passes outside his window.

I have no idea whether the bust has always been painted in these cold colours, but there’s more than a touch of “zombie Shakespeare” about the hue (a zombie Shakespeare made an appearance in The Simpsons’ 1992 Halloween special Treehouse of Horror III, looking surprisingly similar to the pub’s statue.)

The sign outside also claims the bust lost a hand in World War 2 “when a bomb dropped nearby.”

While the bust is definitely one hand down, I’m inclined to take everything that sign says with a pinch of salt.