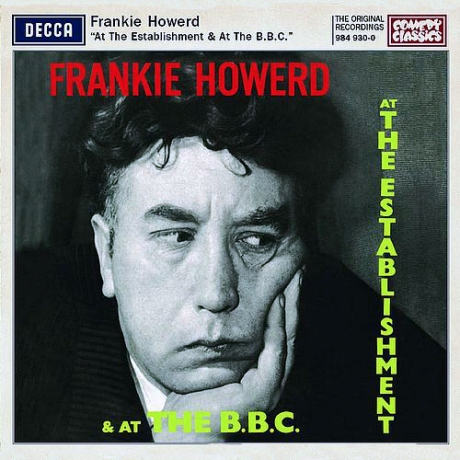

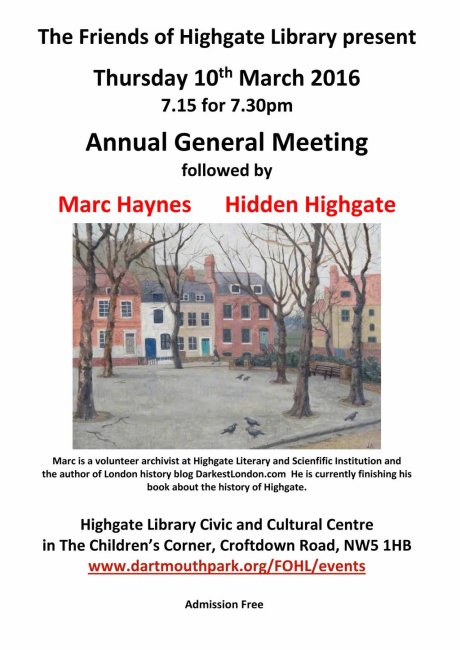

Hidden Highgate talk, 10th March 2016

March 8, 2016

City of London Pubs (1973): Forty Years On – Part 5

November 25, 2014

Please note: I’m jumping ahead here, but the long-delayed Part 1 will follow in the next week!

This is the fifth part of my walk following the route of City of London Pubs: A Practical and Historical Guide by Timothy M. Richards and James Stevens Curl.

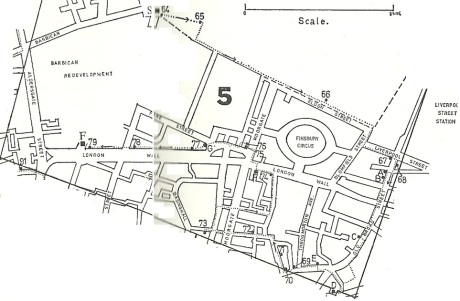

AREA 5: THE BARBICAN, MOORGATE AND FINSBURY CIRCUS

For Richards and Curl, Area 5 was “our largest tour, topographically speaking” – but today, it’s the area which drives home just how much the City has changed in the last forty years.

Once, this area was the heart of the City’s brewing industry. On Chiswell Street stood the Whitbread Brewery, founded by Samuel Whitbread in 1750 as the country’s first purpose-built mass-production brewery. On the wall outside, a stone plaque records a 1787 visit by George III and Queen Charlotte – their visit was commemorated with two rooms used for storing beer named in their honour.

Once, this area was the heart of the City’s brewing industry. On Chiswell Street stood the Whitbread Brewery, founded by Samuel Whitbread in 1750 as the country’s first purpose-built mass-production brewery. On the wall outside, a stone plaque records a 1787 visit by George III and Queen Charlotte – their visit was commemorated with two rooms used for storing beer named in their honour.

The brewery is no longer operating, but it was still a working brewery when Richards and Curl were writing in 1973 – they wrote that Whitbread’s “is now the sole survivor” of the City breweries, which had once been 40 strong – but it closed three years later in 1976.

The real damage to the City’s historic pubs started at this point, but it was really during the 1990s and early 2000s that the trade took a hammering it can never recover from. Bigger profits were to be found outside the pubs: in the value of the land and in other, more profitable, businesses.

The company used the Brewery as their headquarters until 2001, when they decided to wash their hands of the pub trade after two-and-a-half centuries. Their website proudly states:

In 2001 we became the company we are today. We sold our breweries [in 2000] and left the pub and bar business [selling off their pubs in 2001], refocusing on the growth areas of hotels and restaurants. Our reinvention as the UK’s leading hospitality business naturally coincided with the ending of this country’s brewing and pub-owning tradition, started by Samuel Whitbread over 250 years earlier.

Since 1995, Whitbread have owned the Costa Coffee chain, and this, along with Premier Inn and Brewers Fayre restaurants, has been the main focus of their business ever since.

The Whitbread Brewery was sold to an investment firm in 2005 and is now The Brewery, “a premier corporate venue” and “a leading conference space.”

I’ve been there for an awards-do and it’s very pleasant, but I can’t shake the feeling that are lots of other similar corporate venues dotted around the neighbourhood, and it would be far more special if it had remained a working brewery. Of course, that comes down to profit, and if that’s not there, what can you do?

The fate of the Whitbread Brewery was the same as many of the pubs which Richard and Curl visited in 1973, and their writing makes it clear they were largely unaware of the extent of the creeping destruction which was just around the corner.

This walk is close to a tipping point in my survey – this is the first walk where the number of lost pubs far exceed the number which have survived. Five pubs that Richards and Curl visited in 1973 are still here; but ten have gone. The City has lost so many pubs by this point in my survey that nearly half of the pubs which Richards and Curl visited in 1973 have disappeared.

The huge office blocks which now dominate the area have also entirely changed the area’s topography. What used to be a street with numbers neatly along its length has often been replaced with vast glass atriums with company names etched onto the glass, and entire sections of the roads have been replaced by single buildings. Occasionally, this has made it hard to pinpoint the exact locations of lost pubs.

Additionally, there seems to be a concerted effort to hide road names when office blocks have taken over. Many street signs (some of them very old signs themselves) are placed high above the level of the street, often on one side only and at angles that make it almost impossible to see. Why this should be, I have no idea.

No.64 – THE KING’S HEAD, 49 Chiswell Street, EC1

Noting that Chiswell “is probably a corruption of the brewery’s ‘choice well’”, Richards and Curl call The King’s Head the “first of the Whitbread brewery taps…The interconnected saloon and public bars are always bustling, patronised mainly by brewery workers and men from the Barbican site. The small saloon lounge inevitably fills up in no time at all…A large mural depicting the brewery in olden days graces one wall.”

The pub has now gone, replaced with a smart bistro called The Chiswell Street Dining Rooms, which stretches four shop-fronts along the road. There is a bar inside, but it is certainly not a pub – the menu outside sounds delicious, but anywhere offering “prune and Earl Grey tea puree” on the side of a dish is definitely a restaurant.

As is often the case when I wander around the City with a camera, a gentleman who worked at the Dining Rooms came over to ask me what I was doing when I was photographing the building. As soon as I’d said “I do a blog”, he immediately relaxed and told me to pop in for a drink if I fancied. I can tell you that isn’t the usual response I get – some people have asked me for “ID proving you’re a historian”, which I don’t think actually exists – so thanks to him. I didn’t have the drink, but I appreciated the gesture.

No. 65 – THE ST PAUL’S TAVERN, 56 Chiswell Street, EC1

At the junction with Silk Street, on the other side of the Brewery’s entrance from the King’s Head, formerly stood the St Paul’s Tavern, a “popular pub” where “space…is always at a premium.” It has now been renamed the Jugged Hare, and while more obviously a pub than the Chiswell Street Dining Rooms, it is not what anyone could term a boozer.

Looking at the menu outside, I noticed the bottom of the menu has the same details as the one outside the Chiswell Street Dining Rooms, noting it was owned by ‘the ETM Group’. Slightly lower priced than its sister business, it was similarly filled with suited City types and certainly isn’t the sort of place you’d wander into wearing jeans and carrying a copy of the Racing Post.

The problem here is that if it looks what a pub traditionally looks like, it has a bar and it serves a decent pint of beer, is it still a pub? I’ve thought about this a lot for the purposes of this survey, and I’ve come to the conclusion that it isn’t necessarily.

There are certain things which are integral to pubs that go beyond that – could you pop in for a swift half with two mates on the way to a gig? Could you nip inside to keep out of the rain, and nurse a half for the best part of an hour? Would you go there on a Sunday morning to read the papers? Is the bar the focus of the building as opposed to the restaurant? The answer to all those questions is no.

It might seem as if I’m splitting hairs, but I think the main purpose of a pub has to be to primarily serve alcohol to people in a social environment. If the main focus is on food, and not on serving beer, then it’s a restaurant. So while the Jugged Hare looked very nice, it’s not any longer what I think can be termed a pub.

No. 66 – THE RED LION, 1 Eldon Street, EC2

As Richards and Curl state, the Red Lion (like the two previous businesses) is ever so slightly outside the boundary of the City, but aside from saying its busy, they spend little time on the overall look. Perhaps it’s due to the glass cliffs which now tower above it, but the Red Lion looked terrifically inviting from the outside, and more so when I looked through the door.

Run by Taylor Walker, it’s a snug, dark wooden room which was full of pre-Christmas afternoon cheer.

No. 67 – THE RAILWAY TAVERN, 15 Liverpool Street, EC2

“Standing as it does opposite Broad Street and Liverpool Street Stations, The Railway is an obvious place to down a quick pint while waiting for a train. More trains have been missed for this reason than all others put together we suspect. The second of Whitbread’s ‘theme’ houses (owned jointly with Bass), this one is a real Mecca for railway enthusiasts. The large, once stately, lounge houses numerous prints, photographs, and notices concerning railway history. Two models stand out in particular – an LNER Coronation Coach and the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway’s ‘Jenny Lind.’”

While these pieces of railway memorabilia have long gone, The Railway remains, now subdivided into bars: the main one, an upstairs bar and dining room called The Engine Room, and one smaller round the back, named the Citybar – a name that immediately makes me think of 1980s Yuppiedom (perhaps also because it comes complete with a stained glass window reading ‘Wine Bar’ above.)

Not withstanding the handsome sub-classical exterior, the inside is a bit gloomy, with the darkness punctured by the flash of fruit machines, Sky Sports on the flatscreens and an Atom-bomb-bright board on showing rotating adverts for Now That’s What I Call Music compilations and local estate agents. It hadn’t put many people off, as it was busy inside.

Next door, the pub’s proximity to the railway was spelled out: Crossrail’s redevelopments are taking place, but it’s a relief to see the pub incorporated into the developer’s idealised vision of the future of the area.

No. 68 – PATMAC’S RAILWAY BUFFET, 73 Old Broad Street, EC2

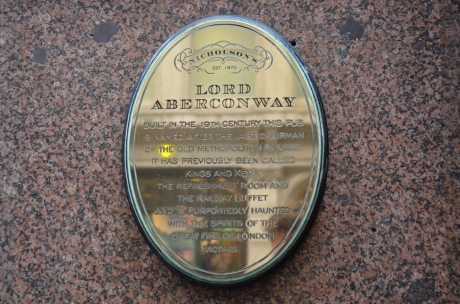

“Essentially, as its name suggests,” wrote Richards and Curl in 1973, “Patmac’s (Patrick & Macgregor) is a buffet bar for Liverpool Street Underground Station…It is interesting to note that Liverpool Street should have a buffet bar here, as it is now the only tube station apart from Sloane Square possessing a bar actually on the platform.” While the Liverpool Street tube bar is long gone, Patmac’s is still operating, although now it goes by the much preferable name The Lord Aberconway.

A lovely Victorian bar – probably the most handsome interior of all the pubs on this walk – it’s run by Nicholson’s, who are one of the few brewers to proudly retell the history of their pubs on handsome plaques outside (I award extra bonus points for mentioning ghosts and/or the plague). The name change – Lord Aberconway was the last chairman of the Old Metropolitan Railway, which amalgamated with other lines in 1933 to form the Underground as we know it today – is relatively recent, but the pub itself (despite the frequent name-changes) looks as if it has been largely unchanged for years.

Letter E – THROGMORTON BAR, 27 Throgmorton Street, EC2

No.69 – THE BODEGA BAR, 30 Throgmorton Street, EC2

Throgmorton Street was, for many years, dominated by the bars along it, serving the workers in the nearby Stock Exchange.

During the 1970s, the Throgmorton Bar was “a darkly-panelled bar in vaguely seventeenth-century style, with ‘period’ plaster ceiling in the Jacobean manner…the showpiece of this bar is, however, undoubtedly the mosaic-clad stairwell that leas down to the basement. The stairs winds it way round an elegant wrought-iron cage containing the lift shaft. The mosaics are richly colourd, with classical Pompeian friezes and much use of gold.” Its near-neighbour, the Bodega Bar, was “a remarkably long, narrow bar…based on a styling vaguely art nouveau. The walls are subdivided by pilasters of alabaster and marble, and the plaster ceiling is enriched with sub-Art Nouveau and Rococo motifs.”

While not doubting Richards and Curl’s appreciation of these places (it sounds a little like the decor of these bars might not be to modern tastes), all have since disappeared over the years as whatever redevelopment is happening in Throgmorton Street continues to not happen.

Unlike most City developments, there are no signs promoting any new developments ‘coming soon’, even though it looks as if the road is definitely being prepared for redevelopment.

Throgmorton’s closed in 2008, the long-running Throgmorton’s restaurant (responsible for the elaborate metalwork along the road, most of it dating from the time the restaurant was owned by the Lyon’s chain) in 2013, and a pub not mentioned in City of London Pubs called The Arbitager was the last to be operating in the main portion of the road.

I went in once a few years back, and it was simply unique – with the racing on, and unpainted walls, it looked more like a Dickensian hole-in-the-wall gin shop than a pub. No less exciting for that. Now it too has gone the way of all the rest.

No.70 – MOORE’S BAR, 34a Throgmorton Street, EC2

At the lower end of Throgmorton Street, where Moore’s Bar once stood – “below pavement level, the subterranean bars are loaded with Victoriana, especially mirror advertisements of the late nineteenth century, stuffed fish and other period bric-a-brac” – the buildings have all been demolished and are awaiting office blocks.

No.71 – BIRCH’S, Angel Court, Ec2

“Chiefly a wine house,” note Richards and Curl, “the shop front, with its three semi-circular leaded windows, is a passable replica of part of the eighteenth-century original [Birch’s wine shop in Cornhill]…the interior is small and intimate, with a board floor. There is a splendid open screen of vaguely Gothick style separating the front bar from the rear alcove containing tables – a most charming feature.” All these features have now gone, along with the historic name – the only business along the street in a building similar to the one Richards and Curl described is the Mint Leaf Lounge, a huge open plan bar which looks a lot of the lobby of an expensive hotel, all honey lighting and strange human-shaped silver statues.

No. 72 – THE BUTLER’S HEAD, 11 Telegraph Street, EC2

New in 1973 – “another undistinguished addition to the City” – this pub has since been replaced by a later office block with a pub underneath called The Telegraph.

By far the largest of all the pubs I saw on this walk – honestly, you could take the tables and chairs out and play a football match inside – The Telegraph is run by Fullers. It’s newness makes it look like a branch of the Slug and Lettuce and it lacks charm – but I suppose its main purpose is to cater efficiently for large numbers of workers on a weeknight rather than act as a cosy local.

Due to the fact that neither Richards nor Curl would recognise this site in the slightest, and the fact the name of the pub which used to be on this site has been lost, I’m counting this as a new pub which has opened on the site of an old one which closed.

No.73 – YE OLDE DOCTOR BUTLER’S HEAD, Masons Avenue, EC3

Set in a beautiful avenue of half-timbered, narrow old houses, this pub was named after Dr William Butler, the Court Physician to King James I. Famous for inventing a popular medicinal ale, the pub which takes his name is old, but was significantly remodelled in the 1920s.

Largely preserved since then, when I visited it had been renamed The Movember Arms to promote the excellent men’s health charity Movember. Hopefully this renaming is just for the month of November – I must admit, it’s so professionally done, there’s a part of me that’s ever so slightly worried it won’t be changing back. Thankfully the barrels hint the name isn’t here to stay…

No. 74 – THE STIRLING CASTLE, 50 London Wall, EC2

“A late nineteenth-century pub with a strongly designed exterior,” wrote Richards and Curl, “somewhat spoiled by the loss of its original glass.” More than the glass has gone now – the entire pub and surrounding buildings have been demolished and replaced with the ubiquitous office block with shop units underneath.

The lack of numbering on this faceless block means its hard to tell exactly where the pub would have been – it looks to be where LA Fitness is. A couple of original metal plaques have been salvaged by the developers and pinned to the front of the modern building like the scalps of defeated enemies – one, which reads ‘SCS 1886’ seems to fit the date of the old pub given by Richards and Curl, with the ‘SCS’ perhaps incorporating the initials of ‘Stirling Castle.’ This is just a guess – if anyone knows any better, please let me know!

No. 75 – THE GLOBE, 83 Moorgate, EC2

“The Globe is one of those pubs that no one knows by its real name; it is universally known as The 199.” While I don’t think anyone knows the pub as The 199 these days, the Globe is still standing, huddled together at the edge of a small group of old buildings kept standing as all the surrounding ones have been knocked down to build offices.

Huddled together amidst the skyscrapers, the Globe is a hardy survivor –“it was mentioned in 1734 in records of the Clockmaker’s Company, and we know that John Wilkes ‘dined at Globe near Moorgate’ in 1770.” Nowadays there don’t seem to be many radicals coming through the doors, only City workers having a couple of pints before heading to Moorgate station just a few wobbly steps away.

No. 76 – THE MOORGATE, 85 Moorgate, EC2

Located directly next door to the Globe in 1973, the inn was once known as The Swan & Hoop, and it was here that the poet John Keats was born in 1795 (his father managed the livery stables at the inn, although whether Keats was truly born here or at his parent’s unidentified nearby house is lost in the mists of time.)

The Moorgate is no longer running, having been swallowed by its neighbour at some point and renamed ‘Keats at the Globe’, although I’m not entirely certain if they are actually connected as a whole. The house bears a plaque commemorating Keats’ birth and the house – not original to the time Keats was born and now looking really tired –probably has its famous connection to thank for escaping the redevelopment which has started one door down. As the pub is now just an overspill of The Globe, I am counting it as lost.

No.77 – THE PLOUGH, St Alphage Highwalk, London Wall, EC2

No. 78 – THE PODIUM, St Alphage Highwalk, London Wall, EC2

No. 79 – THE BARBICAN, St Alphage Highwalk, London Wall, EC2

These pubs were “three new highwalk public houses” located in the Barbican development (which, at the time of Richards and Curl’s 1973 book wouldn’t be completely finished for another three years.) All were situated on the same Highwalk (the name given to the passageways in the complex which were high above street level), all appeared during the early 1970s, and all shut during the 2000s, ahead of a redevelopment of the fringe on which they were situated.

Along with the pubs, St Alphage Highwalk has itself been terminated.

It currently leads nowhere, blocked off at one end and cut off at the other, as ‘London Wall Place’ (another office) is erected on the site where the pubs once stood, alongside a universally unloved late-1950s skyscraper named St Alphage House. The small parade of shops on the site always underperformed and the units had been empty for a number of years. After the recession stalled a number of projects, the parade and St Alphage House were finally demolished earlier this year.

There are still two places to get a drink by the Barbican, however: situated on Moorfields Highwalk is the City Boot…

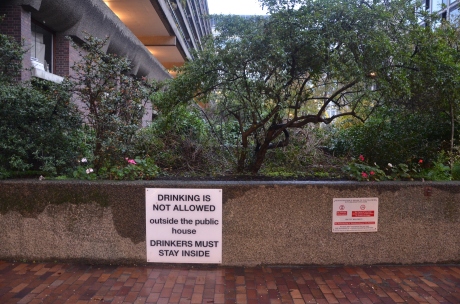

…while close by the Church is Wood Street, a restaurant which also serves drinks. It has a pub sign outside and a snooker table (although with red baize, which I have problems with), so I’m happy to count it as a pub. It was formerly known as the Crowders Well before its current incarnation.

It also has a sign outside that pleased me greatly. “Drinking is not allowed outside the pub. Drinkers must stay inside.”

That’s what people who use pubs should always be. Not customers, not guests, not patrons.

Drinkers.

Two quick notes

In this walk, Richards and Curl also included a number of wine bars (or as they had it, places that were “not a pub in the true sense of the word, but included as a drinking establishment”), which they chose to letter from A to F, rather than number like pubs. All but one of them – Gow’s Oyster Bar on Old Broad Street, which looked like a great place to go at Christmas and was fit to bursting with bald businessmen enjoying a late seafood lunch – have long gone, as, unlike pubs, when the owner left, the business didn’t continue. As such, I have left them off this survey, as I have done with new wine bar/club places, such as Babble City (which looks as if it was specifically designed to scare off anyone over 30) on Wormwood Street.

Additionally, a few proper new pubs have appeared in the forty years since City of London Pubs was written. At no. 26 Throgmorton Street is the Phoenix, a large cavern of a place with dark wood interior…

…and on Wormwood Street sits the King’s Arms, a Taylor Walker pub situated underneath a tower block which must have sprung up in the years following Richards and Curl’s book.

THE TALLY SO FAR:

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs still open: 32 (4 renamed)

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs now closed: 31

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs which had closed and are now open: 1

Pubs opened since 1973’s City of London Pubs: 6

City of London Pubs (1973): Forty Years On – Part 3

June 18, 2014

This is the third part of my walk following the route of City of London Pubs: A Practical and Historical Guide by Timothy M. Richards and James Stevens Curl.

AREA 3: SMITHFIELD AND ST BARTHOLEMEW’S

The majority of the pubs in the area first appeared when the modern Smithfield meat market opened in 1868. With the coming of the railways came the men to work in the market; and with the men came the pubs.

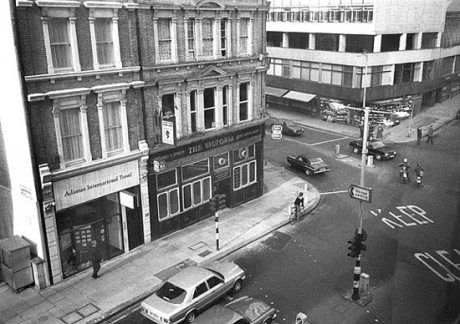

No.32 – THE VICTORIA HOTEL, 25 Charterhouse Street, EC1

In 1973, this pub was one of many in the area which displayed a sign displaying “the vital information that anyone lawfully engaged on business in the market may drink here from the hours of 5 to 8 o’clock in the morning. It is the first of several such signs in the vicinity”, which applied only to the local Smithfield meat-market workers.

While Richards and Curl felt the “main recommendation for visiting the pub itself…is the good-humoured people by whom it is used”, those people are long gone. When I visited, the block where the pub formerly sat had been demolished, part of the Crossrail development dominating the area around Farringdon Tube.

No.33 – THE HOPE, 94 Cowcross Street, EC1

The pub was built in 1790 and much of the character of its Victorian heyday remains intact. It is still recognisable from the description back in 1973 – “an unusual front, with bow window and large fanlight over a granite plinth” – and Richards and Curl celebrated the “encaustic tiles in the corridor and entrance, and fine etched glass panels in the screen separating the bar from the corridor.”

Sadly, when I visited, one of the glass panels in an exterior door had suffered a vast crack from top to bottom. It looks like the sort of damage that’s hard to put right.

No. 34 – THE SMITHFIELD TAVERN, 105 Charterhouse Street, EC1

In 1973, the narrow pub possessed a bar-billiards table, a strange hybrid of pool and skittles – Richards and Curl mention the table was one of the very few to be found in the City, “partly because so few pubs have a space” for it. The bar-billiards table is no longer there, replaced with ordinary tables for diners.

The Smithfield Tavern spent the period from 2006 to 2009 under the name ‘The Wicked Wolf’, and while its original name has been brought back, it still looks as if its attempting to draw in a younger crowd. Most of the original interior has been removed, and when I passed, it had been replaced with record decks, low leather pouffes, and the lowest level lighting I’ve ever seen inside a working building.

Richards and Curl also remarked on the Tavern’s unusual pub sign, which showed “two male figures talking to one another, and from their dress they appear to be Jewish rabbis.” This has since been replaced with a more generic landscape.

No.35 – THE FOX AND ANCHOR, 115 Charterhouse Street, EC1

“In shape, this is the Smithfield’s twin”, but in 2014, the Fox and Anchor (most likely named, according to Richards and Curl “after nearby Fox and Knock Street” – streets which don’t seem to exist, but which I’ve not been able to find any more information about) retains more traditional pub fittings.

Most notable is the “splendid exterior [of 1898]…a complete Art Nouveau facade of moulded cast stone, with coloured decorations very reminiscent of the work of Neatby at Harrod’s meat hall.”

The pub was restored to its original Victorian splendour in 1986, and is today a fine example of that definitive style of pub architecture.

No. 36 – THE SUTTON ARMS, 6 Carthusian Street, EC1

On a road named after the former Carthusian monastery, founded by Sir Walter Manny in 1371 and today known as The Charterhouse, The Sutton Arms is another fine, solid Victorian pub.

The interior had been modernised when Richards and Curl visited in 1973, but the “fine exterior” and “good glazed tiles at the entrance” are still there today. Popular legend has it that the pub is haunted by a red-headed elderly man, nicknamed Charlie, who appears fleetingly before disappearing.

No. 37 – THE OLD RED COW, 71-72 Long Lane, EC1

“The origin of this name is simplicity itself,” wrote Richards and Curl in 1973. “As old red cows are a rare sight in this country, it follows that their milk (beer) is of great value.” Once very popular with market porters, this small pub (the upstairs room is a restaurant, so the pub is just the single downstairs room) is well preserved.

With entrances from two sides, it also has a board explaining its history on the outside wall, making it one of the few pubs to boast about a historical connection with the relatively modern coupling of Bernard Miles and Peter Ustinov.

No 38 – THE HAND & SHEARS, 1 Middle Street, EC1

The Hand & Shears – or “The Fist and Clippers, as it is affectionately dubbed by locals” – is earlier than many of the pubs surrounding it, dating from the early 1800s. In 1973, Richards and Curl called it “relatively unspoilt…an excellent example of a traditional nineteenth-century pub.”

There has, however, been an inn on the site since the Middle Ages – the date above the pub’s entrance proclaims it was established in 1532. A popular inn used by cloth merchants (which gave the pub its name), it was used as the venue to settle disputes and grievances of people who visited the annual St Bartholomew’s Fair – licences were granted, weights and measures were tested, and fines imposed on fraudulent traders. For many years, the Fair was officially opened from the inn’s doorway by the Lord Mayor – but impatient clothiers would later wait at the pub the night before and declare it open on the stroke of midnight, signalling to gathering crowds that the Fair was officially open by waving a pair of shears in their hands.

It was the busiest of the pubs I passed on this leg of the trip, and the people inside looked so jovial. It’s the only one I didn’t have a drink in that I wish I had.

No.38b – THE RISING SUN, Rising Sun Court, EC1

Richards and Curl mention The Rising Sun in passing – “although the old pub of that name is still visible, it no longer rings to the sound of voices.” Today, in a surprising turn of events, the pub that had been closed in 1973 has come back to life.

Hidden away in a quiet street, it’s a welcoming little pub with a vast stretch of frosted windows making up two entire sides of the inn.

It is the only pub featured in City of London Pubs to have come back from the dead.

No. 39 – THE BARLEY MOW, 50 Long Lane, EC1

A Victorian pub, by 1973 it had become “a ‘modern-traditional’ pub,” wrote Richard and Curl, “camped up with panelled walls, wooden bar, restrained colour scheme, and good cast-iron tables.”

Today, the Barley Mow is an Italian restaurant, Apulia. At the top of the building’s facade, the old pub’s name can still be seen.

No. 40 – THE RUTLAND, 9-10 West Smithfield, EC1

“Every so often one stumbles across a particular brewery’s only house in the City, and The Rutland is Shepherd Neame’s sole representative”, wrote Richards and Curl in 1973. The pub is still here, but has been renamed The Bishop’s Finger, after one of the Shepherd Neame brewery’s most popular beers.

Apart from the name change, the pub is much the same as it was in 1973, when Richards and Curl admired the exterior and “three cast-iron columns with fine capitals”, but noted “nothing else remains of the original decor.”

No. 41 – THE COCK TAVERN, Central Markets, Smithfield, EC1

In 1973, the Cock Tavern sat in two subterranean rooms beneath the Central Market , “utilitarian to the extreme.”

It catered primarily for the porters, with opening hours from 5.30pm to 3pm, and its alcohol licence coming and going through the day – it opened at 5.30am to sell only food, was able to sell alcohol from 6.30am, but then from 9.30am to 11.30am could only sell food, and was once again able to sell alcohol from 11.30am until closing time at 3pm.

Even though it had become very popular due to its inclusion in lots of articles about ‘Secret London’, the Cock’s purpose was lost when the Market closed and it shut its doors for the final time in 2013.

No. 42 – THE NEWMARKET, 26 Smithfield Street, EC1

Now an upmarket gold-and-black bar called Bird of Smithfield and offering ‘libations’ instead of pints, in 1973 The Newmarket was a saloon bar boasting a “glass mirror along one wall…engraved with a horse-racing scene.” It seems likely this was an error by a later owner, who didn’t realise the pub had been named after the new meat market outside, rather than the horse racing course.

Upstairs in 1973 was “a large mural of the old open-air market”, but I was unable to see if this remains.

No. 43 – THE WHITE HART, 7 Giltspur Street, EC1

“Here is the most lavish pub encountered for some time,” wrote Richards and Curl, “with heavily upholstered seats and settees, low coffee-type tables, a Black Watch tartan carpet, soft music, and subdued lighting.”

This lavish 1907 pub is now gone and has been turned into offices – the only reminder of its former use is the antlered stag head above the doorway.

No. 44 – THE VIADUCT TAVERN, 126 Newgate Street, EC1

Richards and Curl were delighted by this pub in 1973: “Named, of course, after Holborn Viaduct…the pub is a splendid example of Victorian design. This is a full-blown corner pub, built on a curve, with glazed ground floor. Inside are wooden screens, finely carved, with exquisite engraved glass panels of folitate design. There is wonderful ornate gilded and silvered glass by the staircase, and a manager’s stall, with an ornate pulpit-like exterior, cornice and clock, and engraved glass, some curved.”

Today, the Tavern is much the same, but the road outside is so busy with traffic thundering past that the smokers might as well have been standing on the hard shoulder of the M1.

No. 45 – THE MAGPIE AND STUMP, 18 Old Bailey, EC4

Standing in an alleyway opposite the Old Bailey, during the eighteenth century, the pub hired out the upper rooms to people wanting an unobstructed view of the executions in Newgate prison, which stood opposite.

The practice continued under 1868, but a reminder can be seen on the board outside – promoting “Last Pint Friday”, it’s a half-price offer ‘commemorating’ the pub’s tradition of sending a final pint to condemned men.

In 1973, Richards and Curl admired the “dark panelling, leaded windows, carpeted floor and winged bench seats” of the pub, which had been rebuilt in 1931. None of these remain today, and the pub has the rather cold look of a wine bar – black furniture, checkerboard patterns on the floor, and grey feature walls.

No. 46 – THE GEORGE, 25 Old Bailey, EC4

No.46 – THE RUMBOE, 27 Old Bailey, EC4

The George was a nineteenth-century pub, the Rumboe amid-twentieth century one (its unusual name came from a ‘posh’ name for Newgate Prison used by thieves) but both have been entirely swept away by a large new office development, New Ludgate.

The developers call it “a striking contemporary addition to one of London’s most historic locations.”

THE TALLY SO FAR:

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs still open: 27 (3 renamed)

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs now closed: 19

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs which had closed and are now open: 1

Note: surprisingly, there are two pubs which have opened up in Smithfield since City of London pubs was written – and I say ‘surprisingly’ because I thought they’d been there for years.

The Fuller’s Ale and Pie House and the Butcher’s Hook and Cleaver on West Smithfield have the look of long-established Victorian pubs, but they were opened in November 1999 (Fuller’s own both, so while they look distinct, perhaps they should count as a single pub divided into two.) They replaced the two properties there previously, a meat wholesalers and a branch of the Midland Bank.

NEXT UP: AREA 1!

City of London Pubs (1973): Forty Years On – Part 2

April 24, 2014

This is the second part of my walk around the pubs detailed in City of London Pubs: A Practical and Historical Guide by Timothy M. Richards and James Stevens Curl. Area 1 is below!

AREA 4: CARTER LANE AND SOUTH OF ST.PAULS

No.48 – THE SEA HORSE, Queen Victoria Street, EC4

“Goodness knows why this modern, one-roomed pub was named The Sea Horse,” marvel the authors, who go on to call the then-newly-built pub “an afterthought…with little character.”

Thirty years on, the Sea Horse looks positively quaint, a strange survivor jutting out on a busy road full of anonymous office blocks. With one open room inside, pale wood flooring and with light flooding in through the curve of windows, it’s more charming today than when Richards and Curl found it.

No.49 – THE HATCHET, 28 Garlick Hill, EC4

Described in 1973 as “a good little local”, the Hatchet appears not to have changed much over the last forty years (aside from the cigarette bins fastened to both entrances). The authors suggest the unusual pub name cames from a tool used for trimming wood, a timber harbour once operating on the Thames at the foot of Garlick Hill – but another more recent source claims it took its name from the Hatchet Fur Trading Company, although I’ve been unable to find out anything about them.

Even more pleasingly, stepping inside is like stepping back in time. The nicotine-coloured lights, the racing on the telly, a couple of ornate mirrors, the silent man propped up by the bar – the Hatchet looks more like it belongs in 1973 than 2014, and is all the better for it.

No.50 – THE QUEEN’S ARMS, 30/31 Queen Street, EC4

In 1973, the Queen’s Arms was “a friendly little local” with an elegant three-story facade “with Edwardian bows of wood, delicately moulded and panelled” and above, “rubbed and moulded brickwork of excellent quality.” It was one of the few buildings in the immediate area not to have been bombed during the Second World War – the neighbouring properties were both hit, leaving the pub as a detached building.

Inside was both public and saloon bar, “a small portion of glazed tiles of superb quality” and “two arches of fantastic enrichment, polychrome and elegant.” CAMRA called it a “rare basic City pub” and drew attention to its semi-circular bar, “unique in the City.”

As far as I can tell, the Queen’s Arms was demolished some time in the 1990s. This office block – with a Dominos Pizza on the street level – now stands on the site.

No. 51 – THE CROWN AND SUGAR LOAF, 14 Garlick Hill, EC4

“A distinctly informal little pub” which Richards and Curl found to be “an almost exclusively male haunt”, the name of this old inn suggested a connection with the local sugar refineries, which were operating from the 1600s until as late as 1830.

In 1973, Richards and Curl stood outside the pub on Garlick Hill and looked down to see “a truly sad sight – the closed and shuttered White Lion and King’s Head & Lamb. [Upper Thames Street] is about to become a dual carriageway necessitating these demolitions, and so a brand new pub [the Samuel Pepys, no.52 in their book] has been opened by way of compensation.”

Today, nothing remains of the Crown and Sugar Loaf – a new office building has obliterated any trace of it.

No. 52 – THE SAMUEL PEPYS, Brook’s Wharf, 48 Upper Thames Street, EC4

One of just two City pubs to overlook the Thames, the Pepys dates to the early 1970s, near new when Richards and Curl popped in. In the book, they’re quite respectful about the heavy-handed themes they found within.

The upstairs bar had “a sea-going atmosphere”; the downstairs Chandler’s Bar “has been designed to create the atmosphere of a working warehouse”; and the restaurant reflected Pepys’ romantic life, with tables “set in curtained alcove named after the inns and taverns to which he took his lady loves” and a facsimilie four-poster bed. Undoubtedly that restaurant seemed the height of sophistication in the early 1970s.

The pub itself is not easy to spot. Located down the end of a dark alley, and inaccessible from the riverside walk, it’s not really somewhere you happen to chance upon, and the lack of a bar to peer into (the entrance door reveals a carpeted flight of stairs leading upwards, with signs urging the visitor to come up) means it’s easily missed.

No. 53 – THE HORN TAVERN, 31/33 Knightrider Street, EC4

I never really understand why people change the names of historic pubs. Since City of London Pubs was written, the Horn Tavern – “a very old house and mentioned in Dickens’s Pickwick Papers”, as well as Pepys’s diaries and drawn in the 1960s by Geoffrey Fletcher – has been renamed the Centre Page.

Even more perplexingly, it’s not as if the owners were unaware of the inn’s historical importance – the pub’s former name is painted on the front alongside the new one.

Similarly, a sandwich board tells you the name of the pub, adding underneath “Formerly the Horn Tavern, earliest recorded date 1663.” Even more remarkably, the pub’s website has a page dedicated to the history of the Horn (which is great to see – more pubs should do this.) I just can’t understand why someone chose to jettison a heritage that clearly they’re proud of.

The Centre Page has an enviable location sandwiched between the Thames and St Pauls – but the pub is long, low and hemmed in by buildings, meaning on even a bright day, its shrouded in shadows and as the bar has been sunk beneath pavement level, it looks somewhat gloomy inside.

No.54 – THE BELL, 6 Addle Hill, EC4

Richards and Curl called the Bell “a friendly, intimate pub” with an exterior being “a very fine, strong example of traditional pub design.” It had closed by the late 1980s, as redevelopment schemes for office space flattened vast parts of the City. Today the road is dominated by a stark cliff-face and dozens of idle BT vans.

No. 55 – THE RISING SUN, 61 Carter Lane, EC4

“A friendly, domestic little ale-house”, the Rising Sun is still standing and still busy. It looks lovely inside – a big room decorated well. Hanging baskets are always a sign that a pub will be worth a visit.

No. 56 – THE COCKPIT, 7 St Andrews Hill, EC4

Of a similar vintage to the Rising Sun, the Cockpit has an unusual layout – the bar is on a higher platform than the rest of the pub, “which heightens the impression of sitting in a pit” (as the name suggests, a cock-fighting pit was once on the site.) Like the Centre Page, the Cockpit hasn’t always had its present day name – in 1973, Richards and Curl noted that “until recently” it was called the Three Castles.

The outside of the pub is more spectacular than the inside – the two heavy wooden curved doors at the entrance make the lower portion of pub look like it was constructed along similar lines to a Tudor galleon.

The Cockpit was surprisingly busy for a weekday afternoon when there was no big sporting fixture on – it was easily the busiest of all the pubs I went into, with the exception of the much larger Black Friar.

No. 57 – THE BAYNARD CASTLE, 148 Queen Victoria Street, EC4

Named after Ralph Baynard, one of William the Conqueror’s men who built a large fortress on the site (which was consumed in the Great Fire of 1666 although some remnants could be seen in the pub), the Baynard Castle was still standing in the 1990s.

After a spell under the name ‘Cos Bar’ – the conversion an attempt to attract a younger City clientele – today the Baynard Castle is a bar called Rudds. Having looked at their website (I didn’t feel well-dressed enough to go in) the interior of Rudds boasts shiny lager taps, reproduction Louis XIV chairs in the restaurant, and blocky purple sofas.

No.58 – THE BLACK FRIAR, 174 Queen Victoria Street, EC4

Richards and Curl don’t hold back in their praise for The Black Friar – and nor should they. It is, as they state, “the finest example of turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau design in London.”

The building was designed by architect H. Fuller-Clark and artist Henry Poole, both committed to the free-thinking of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and was erected in 1905 on the former site of a Dominican Friary (which had been closed during Henry VIII’s Dissolution.)

The building was designed by architect H. Fuller-Clark and artist Henry Poole, both committed to the free-thinking of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and was erected in 1905 on the former site of a Dominican Friary (which had been closed during Henry VIII’s Dissolution.)

A treasure house of design – everywhere you look, there are carvings of monks, copper faces, mosaics, frescoes, statues, mottoes, signs – the Black Friar is one of the pubs you pass more often that you go in. But inside it’s like a minature V&A – only better because you can not only enjoy the surroundings, but they also serve drink.

The exquisite signs outside…

…lead into to an interior that is just breathtaking.

…lead into to an interior that is just breathtaking.

It is, without doubt, the most beautiful pub in London.

Past the main bar is the biggest treat of all – an alcove, now used as the restaurant.

Decorated in bronze and stone, it is absolutely festooned with statues, inlaid copper medallions and mottoes: “A good thing is soon snatched away”, “Seize occasion”, “Haste is slow”, “Wisdom is rare.”

In each dark corner of the alcove lurk devil-like figurines, representing Literature, Music, Drama and Painting, while figures over the lamp brackets (which are dim) depict the Morning, Evening, Noon and Night. While my camera has brightened the dark alcove, the effect of the gloom means it’s hard to properly make out the sinister shapes you can half-glimpse in the corners.

In each dark corner of the alcove lurk devil-like figurines, representing Literature, Music, Drama and Painting, while figures over the lamp brackets (which are dim) depict the Morning, Evening, Noon and Night. While my camera has brightened the dark alcove, the effect of the gloom means it’s hard to properly make out the sinister shapes you can half-glimpse in the corners.

And as if that wasn’t enough, there’s an equally impressive second bar on the other side of the building.

Incredibly (but perhaps unsurprisingly), the Black Friar was threatened with destruction in the 1960s (to make way for a road, naturally.) It was only saved by a strong opposition movement spearheaded by Sir John Betjeman, and it is now Grade II listed. If you’ve not visited this masterpiece, go.

No.59 – THE QUEEN’S HEAD, 31 Black Friars Lane, EC4

Once “the only building left standing in the whole of a large derelict bomb site”, the Queen’s Head was demolished in 1999 to make way for yet another office complex.

The building with the dark doors in the distance of the photo was formerly a “bar and eating house” called The Evangelist, which closed in 2009 (it still appears when you search for Black Friars Lane on Google Streetview).

THE TALLY SO FAR:

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs still open: 17 (2 renamed)

Pubs covered in 1973′s City of London Pubs now closed: 13

NEXT UP: AREA 2!

City of London Pubs (1973): Forty Years On

March 13, 2014

City of London Pubs: A Practical and Historical Guide was published in 1973. A charming gazetteer written by Timothy M. Richards (“a public-house manager with a keen interest in the history of pubs”) and James Stevens Curl (“an architect with ‘a great interest in pubs, taverns, inns and drink’”), the content is both historically thorough and winningly casual as the two men catalogue the pubs of the City, which, as the cover states, “has, in fact, a higher density of pubs than any other comparable area in England, Scotland or Wales.”

Throughout the book, the two gently hammer home that the only way to truly enjoy the City pubs – while they may be beautiful, architecturally impressive or historically important – is to drink in them. This mission statement is launched with a quote from GK Chesteron’s A Ballade of an Anti-Puritan:

Is it not true to say I frowned,

Or ran about the room and roared;

I might have simply sat and snored –

I rose politely in the club,

And said “I feel a little bored;

Will someone take me to a pub?”

“Follow us!” Richards and Curl reply.

The book “takes the form of several pub crawls which even the most dedicated imbiber would need days to complete.” Richards and Curl split the City pubs into ten areas, “each area including a manageable number of pubs.” A manageable pub-crawl was clearly a more serious undertaking in 1971: the shortest crawl the book suggests is fourteen stops, the longest 23.

Perhaps this explains why their acknowledgements at the end of the book thank the person who typed their manuscript “from a less than tidy original”, and the police “for their good humour.”

When I first picked up the book and got stuck into it, it was a surprise to realise it was written 43 years ago. It certainly doesn’t read that way. In fact, I can’t think of a better book about the City’s pubs – or any guide to pubs, for that matter – than this one.

“Many books have been published concerning the City churches and the famous public buildings and even one dealing with the loos,” the authors write in the foreword. “But there is no comprehensive guide…After all, there are about 200 drinking establishments in the City, including wine bars, and these are well worth a study in themselves. Many older books, while devoting whole chapters to the City, are unfortunately out of date, or too clumsy.”

But while it isn’t ever clumsy, City of London Pubs has sadly joined those out-of-date books. The authors were only too aware of this inevitable fate – in the introduction, they clearly state “the information in this book is correct at the end of December 1971. As far as possible subsequent changes have been incorporated, but these cannot be guaranteed.” Their appendix demonstrated just how quickly things changed: it lists four pubs featured in the main body of the book, which had been demolished by the time of publication.

Thankfully, some of the gloomy apprehensions they raised about the future of pubs in the City have not been realised.

The seemingly unstoppable rise of the City wine bar was a twenty-year fad, and today many of these invaders have been supplanted in turn by branches of Itsu, Pret A Manger and vast corporate headquarters.

Richards and Curl lamented that “the traditional inn signs are fast giving way to neon atrocities”, but this too turned out to be a passing craze.

They also complained of a new ill: inexperienced barmaids, used only to pouring lager through a tap, who refused to pour natural beers into glasses and instead expected customers to come round the bar to do it themselves. They feared the solution to this problem would be pubs “refusing to stock the last few real beers containing sediment in the bottle. Despite a touch-and-go period in the 1980s when lager looked like it would batter bitter into submission, the demise of real ale never came to pass –today, you can probably get more varieties of natural beer in London that at any other point in its history.

In March 2014, I set out to walk in the footsteps of City of London Pubs, to see what changes have happened in the forty-three years since it was published. In an exact reverse of Richards and Curl’s work, I’ve kept my written notes to a minimum but have included photos of each pub (or if its been demolished, whatever’s replaced it.)

The main change I noticed, apart from the demolition of a number of pubs, is the total abscence of separate bars – the public bar, the saloon bar – some of which the book mentions were still in situ in the 1970s but all of which have since been removed.

Should you happen to have a copy to hand, this entry covers Richards and Curl’s first and fourth areas, which covers the ground from Fleet Street to Southwark Bridge (despite the numbering, Areas 1 and 4 border each other.) The numbering of the pubs is the same as it appears in the book.

AREA 1

No. 1 – YE OLDE COCK TAVERN, 22 Fleet Street, EC4

Like many pubs in the City, Ye Old Cock Tavern boasts a connection with Pepys (who visited in April 1668 with the actress Mrs Knipp, where he “drank, ate a lobster, and sang, and mighty merry”), but the present building is a relatively recent home dating from the mid-1880s. Previously, The Cock was situated in Apollo Court, on the opposite side of Fleet Street – the opening of a new branch of the Bank of England forced the move.

The dark, rather cavernous pub remains much as described in the book.

No. 2 – THE CLACHAN, Old Mitre Court, Fleet Street, EC2

A modern pub “with a small upstairs bar and a large dive bar and restaurant” built close to the site of the ancient Mitre Inn (Dr Johnson’s ‘place of frequent resort’), this has disappeared since the book was written – indeed, the lack of a specific address in the tiny square makes it hard to tell where it originally was. The only thing which remains is the Bishop’s Mitre above the door of a spectacularly boring looking office opposite.

No.3 – EL VINO’S, 47 Fleet Street, EC4.

One of the most famous of London’s drinking establishments, “the suitably sombre and discreet” El Vino’s is still going strong.

No. 4 – THE WELSH HARP, 3 Temple Lane, EC4

Back in 1971, the Welsh Harp was “a large pub of four storeys, the ground floor having an arcaded treatment of late Victorian date. Above, the stock-brick facade has rubbed red-brick arches over the windows, and there is a plain crowing cornice.” In 2014, there is absolutely no trace left of the pub but the “arcaded” ground floor can still be seen.

Bar the ancient looking stone bumper on its corner (which is clearly still protecting the building from the side-swiping construction lorries constantly winding through these narrow roads), the building in its place felt so uninspiring, I forgot to even see what it was.

No. 5 – THE WHITE SWAN, 28-30 Tudor Street, EC4

In 1971, the White Swan, with its interior “in mid-1930s style”, was “a good homely local, known to everyone as The Mucky Duck.”

In 2014, it has gone – in its place is a sandwich / salad bar with the not particularly sandwichy-salady-bar-name of ‘Hilliard’. On each side of the door remain two stone white swans, the only reminder of the building’s former life.

Since the 1970s, even the road layout has changed. Where the White Swan was once the corner building on Tudor Street, Tudor Street no longer exists – its former route is now covered by the vast monolithic offices of an international global law firm.

No. 6 – THE HARROW, 22 Whitefriars Street, EC4

While the divided bars that were present in 1971 have been removed and numerous internal refits have been performed over the years, the Harrow is still serving. Unusually, it has entrances on both sides of the pub – front and back.

No. 7 – THE COACH AND HORSES, 35 Whitefriars Street, EC4

A pub with an original late Victorian facade, it had been modernised by 1971 so that “the charming front is all that remains.” Today, the pub – or as the front has it, “local beer house” – has changed its name from The Coach and Horses to The Hack and Hop, presumably a late nod to the area’s journalistic history. Having walked the whole of the area, this is the only contemporary-looking pub-restaurant I came across.

No. 8 – THE TIPPERARY, 66 Fleet Street, EC4

Proclaiming itself “London’s oldest Irish pub”, the pub was opened on the site shortly after 1883 (although the name The Tipperary is more modern.) In 1971, it was “a long, narrow pub in traditional Irish urban style, with rich, dark panelled walls; engraved green glass panels with gilt lettering advertising whiskey and stout; carved display stands; mirrors; and resplendent lamps.” It’s largely the same four decades later.

No. 9 – THE FALSTAFF BAR, 67 Fleet Street, EC4

A “small, narrow bar in the basement of a restaurant” which was all that remained of a “once much larger house called The Falstaff, which closed in 1971”, there was absolutely nothing to signify any bar had ever existed on the site in 2014.

No. 10 – YE OLDE CHESHIRE CHEESE, Wine Office Court, 145 Fleet Street, EC4

One of the capital’s best known inns, it is probably the last pub in the City which will ever be changed. While the tourists enjoy the smoky fires and the faux-grubbiness inside, it’s worth taking a moment to admire the less remarked-upon exterior “with its sash windows, wooden panels, fanlight, and great hanging sign…an excellent example of the sort of pub front that existed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.”

No. 11 – THE KING AND KEYS, 142 Fleet Street, EC4

Almost next door to the Cheshire Cheese, in 1971 the King and Keys could boast a ceiling which “lowered by means of large wooden square” and which “incorporates lights and two applicable motifs. One is a rose, crossed keys, and a knight’s head; the other an orb, crossed maces and a crown.” The pub closed in 2009, and the building is now a Mexican takeaway snack bar.

No. 12 – THE COGERS, 9 Salisbury Court, EC4

In 1937, the eighteenth-century inn (whose name came from the Ancient Society of Cogers, a debating group who made the pub their home) was reincorporated into a modern building built for Reuters by Sir Edwin Lutyens. In 1971, Richards and Curl reported that the Cogers was large and “very much of its period…subdivided spaces give it a pleasant atmosphere…the screens have opaque glass set in; leaded lights are provided, even in the doors; and the bar is panelled, with rails.”

Today, the pub has disappeared – in 2009, the redevelopment of the building saw it replaced with a Sir Terence Conran-designed restaurant called Lutyens. The restaurant is actually on the other side of the road from where I took this picture – when I saw the restaurant, part of the grand deco building, it didn’t strike me that a pub could ever have been there. It was only later I was able to place where it was – so until I go back, here’s the view that the Cogers used to look out on.

No. 13 – THE OLD BELL, 95 Fleet Street, EC4

Originally built in 1670 for Sir Christopher Wren’s workmen, who were rebuilding St Bride’s after the Great Fire of London in 1666, the pub has changed its name numerous times over the centuries. The glass window which Richards and Curl admired in 1971 is still present in 2014, and the pub itself is little changed.

No. 14 – THE RED LION, Poppins Court, EC4

In 1971, Richards and Curl admired the Red Lion, “a decent three-storey building…good panelled ceiling and mirrors contribute to the late Victorian atmosphere…the dark wood of exterior and interior, yellowed walls and old ceiling all bear witness to a distinct lack of youth.” They also noted that “above the alleyway’s entrance one can still see the original tavern sign with a popinjay (a corruption of which gave the court the name Poppins) or parrot carved in stone.”

In 2014, all this has been comprehensively wiped away. The gap between the buildings is still called Poppins Court, but it couldn’t look any less like a Court, or any more like a service road cowering in the shadows of the towering office block it serves.

No. 15 – THE PUNCH TAVERN, 99 Fleet Street, EC4

Largely unchanged since 1971, the Punch Tavern has some lovely brassy Victorian plasterwork and decor – the closest one comes to seeing a gin palace on this walk.

Carvings of Punch and Judy above the bar, paintings of Toby the Dog in the tiled mosaic entranceway, a great glass skylight, dark wood and mirrors everywhere…

…but as Richards and Curl pointed out 40 years ago, “originally the space would have been subdivided and much more intimate in character. It is far too open and almost intimidating now.” It may be too open, but it’s not intimidating – when I went in, the staff couldn’t have been nicer and the clientele consisted of a few businessmen and two women with babies eating lunch. That said, it’s hard to deny that the entrance is much more fun than the inside.

No. 16 – THE ALBION, 2-3 Bridge Street, EC4

Still open, the Albion is still “a popular lunchtime rendezvous for eating, set within an undistinguished late-Victorian building.” When I walked past, even though it was gone 3pm, it was still full of City workers stuffing sausage and mash into their mouths.

No. 17 – THE ST BRIDE’S TAVERN, Bridewell Place, EC4

Up past a huge Premier Inn – the largest one I’ve ever seen, it looked like a terrifying battleship – is St Bride’s Tavern. In 1971, the authors of City of London Pubs said it was the type of comfortable pub which could become anyone’s local – but it’s a rather severe building which today hides a fairly unremarkable interior. It was the only pub I passed in the entire walk which was empty when I looked in. Good for the rest.

THE TALLY SO FAR:

Pubs covered in 1973’s City of London Pubs still open: 10 (1 renamed)

Pubs covered in 1973’s City of London Pubs now closed: 7

NEXT UP: AREA 4!

Darkest London’s 50,000th view

September 26, 2013

Hello!

Today, the Darkest London blog registered it’s 50,000th view. That seems like quite the milestone, so I just wanted to say thanks to everyone who’s read, commented or helped me out.

If you’re a regular follower of this blog, you might be rather irritated about it’s lack of updating. I’d love to be able to do more, but it’s having to sit on the back-burner at the moment – the reason for this is that I’ve been working on a book on a specific area of London which has taken up much of my free time. Hopefully, that tome (and, yes, it’s a tome, it’s huge) will be out by the end of the year. It’s very similar to some of the pieces on the site, but concentrated on one single area – it’s been a struggle not to put some of the stuff up here immediately, but I hope it’s worth the wait.

Once that’s done, I’m starting work on the first Darkest London book proper. It will contain a lot which is akin to the stuff on this site, and hopefully there’ll be a new one each year, like a bumper fun annual.

So thanks for reading, and I’ll endeavour to post more frequently in the run-up to Christmas!

Next up: the story of TFI Friday’s table top and the Hyde Park Pet Cemetary.

Marc

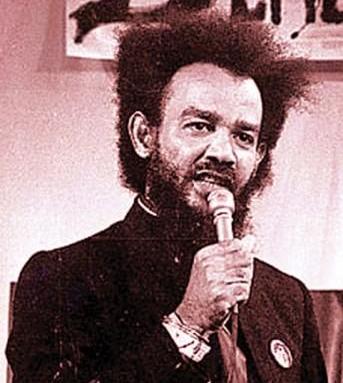

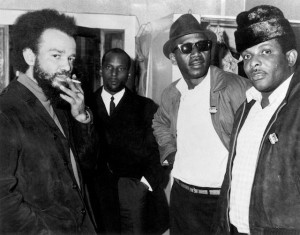

Michael X and the Black House of Holloway Road

June 17, 2013

Not far from Highbury and Islington Station, numbers 95-101 Holloway Road look much like the rest of the houses stretching to either side – unloved, grubby Victorian piles with transient shops underneath: day-glo internet cafes, small lawyers specialising in immigration issues, greasy spoons which have seen better days.

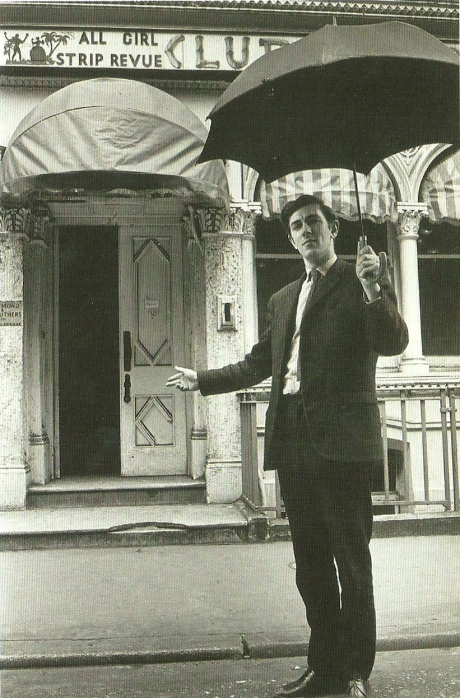

Situated above the Wig and Gown pub, here’s nothing to show that, forty years ago, these houses were briefly the heart of radical black Britain.

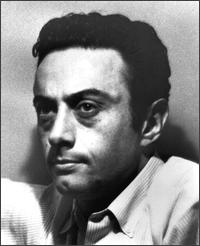

The Black House was the brainchild of Michael X, a man of many contradictions. A published author, firebrand community leader and darling of the left-leaning avant garde, he was also a pimp, conman and megalomaniac who would later be hanged for his part in two brutal murders.

Born in Trinidad in 1933, the charismatic Michael de Freitas was a seaman when he docked at Cardiff in his mid-twenties and decided to stay in Britain. With job opportunities for West Indian immigrants solely of the dogsbody variety – working in car factories or in the bus garages – he became a pimp, living off the earnings of his girlfriend, and when the relationship ended, moving onto other women.

By 1957, with Cardiff unlikely to make him his fortune, he moved to Bravington Road W9, between Kilburn and Ladbroke Grove, with a prostitute named Sandra. Like many young immigrant men with few opportunities, de Freitas found no alternative but to hustle: getting back into pimping, organising gambling rackets with limited success, and taking part in a scam stealing luggage from the West London Air Terminal in Cromwell Road.

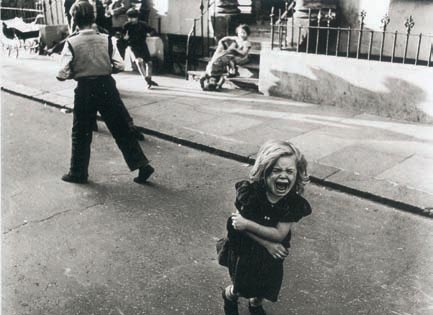

In 1958, DeFreitas moved to Southam Street in Notting Hill with his partner Desiree.

The future Labour Shadow Chancellor Alan Johnson was born in the street at the same time (his 2013 memoir This Boy tells the almost unimaginably bleak story of his childhood in this Notting Hill slum), and the photographer Roger Mayne photographed the road between 1958 and 1961.

As he wrote in his 1968 autobiography, From Michael de Freitas to Michael X:

It was impossible to believe you were in twentieth-century England: terraced houses with shabby, crumbling stonework and the last traces of discoloured paint peeling from their doors, windows broken, garbage and dirt strewn all over the road, every second house deserted, with doors nailed up and rusty corrugated iron across the window spaces, a legion of filthy white children swarming everywhere and people lying drunk across the pavement…

As Desireee told David Peace, “Southam Street was rough, but black people expected that. You were lucky you had a room and nobody bothered you if you paid your rent.”

In the Notting Hill of the 1950s, two social groups of outcasts came together: the recent West Indian immigrants and the working-class white prositutes. Larry Ford, a sometime club owner and contemporary of de Freitas, noted that “you get two outcasts, social outcasts, the blacks and the prostitutes and these two get together and the money comes in.”

In his autobiography, de Freitas wrote about a woman named Sylvia, who he acted as a pimp for (although he claimed she simply turned up with £40 one day, handed it over to him, and their working relationship began from there.) He coldly pondered his position: “People have been trying to work out why prostitutes need a ponce since the profession began and nobody’s found a satisfactory answer. In this girl’s case I think she was a compulsive giver and she had no other way of making so much to give.” Sylvia certainly found someone who would take as much as she could make.

As De Freitas pimped, he quickly became well-known on the semi-criminal scene for the long hours his girls worked (“the way they saw it was that I sent the girl out to work and allowed her to do nothing but to stay on the job constantly. In fact, of course, she seemed to want to do nothing else” he wrote, probably entirely fictionally.)

But during the summer of 1958, Notting Hill sporadically exploded in incidents of violence. Carribean men were being attacked and beaten on the streets by large groups of white men, the flames of racial hatred fanned by Oswald Moseley, the Union movement and the White Defence League, whose motto was ‘Keep Britain White.’

Outside the Calypso Club on Westbourne Park Road, a meeting was held. As three West Indians addressed the crowd, urging them to start committees and write to their MPs to protest against the indiscriminate attacks and the rising tide of racial hatred, DeFreitas asked to speak. It would be his first ‘political’ speech.

He told the crowd “You don’t need committees and representations. What you need is to get a few pieces of iron and a bit of organisation so when they come in here we can defend ourselves.” There was a roar of support and Michael led an attack on a local club used exclusively by white criminals – “some of us lobbed petrol bombs in the back of the buildings while the rest waited in ambush out front.”

Surprisingly, de Freitas didn’t think the two weeks of sporadic clashes and violence now knwon as the 1958 Brixton race riots – which he could easily have claimed a leading role in – were racially motivated. DeFreitas believed the race angle was a creation of the press – “in general people just drifted into violence, finding themselves involved without knowing how or why.” Much like the riots of 2011, he believed “there’s always a large section of any population which is attracted to riots for kicks and to relieve the boredom of their dull lives. With a few wild ones throwing bottles everyone tends to get involved.”

He thought the racial element was only introduced as “white people don’t run to the blacks for protection, nor the blacks to the whites. They separate into their own colour groups, And there you have it, created out of nothing – a race riot. Or, at least, the atmosphere of a race riot. In actual fact, there still wasn’t much real action.”

Following the unrest of the summer came a wave of left-wing, middle-class, liberal, mainly young do-gooders who flooded into the area to try and help the minority population. DeFreitas was frequently in the mix, showing parties of MPs around the “real” Notting Hill.

Around this time, he also worked for the landlord Peter Rachman, having impressed Rachman when, as a tenant, he not only took him on in a tribunal to get his rent lowered, but attempted to start an entire campaign against his empire. Refusing to be cowed by Rachman’s heavies who called round, Rachman decided to take another tact: he offered DeFreitas a job. DeFreitas took it, and Rachman went on to help him speculate in property (Michael moved into the top floor of one of the houses he bought in Colville Terrace, operated a brothel in the basement, and opened up a gaming house in the basement of a property in Powis Terrace.)

When he saw Rachman was selling off his properties, DeFreitas thought he must have some sort of insider knowledge about the market, so he sold Colville Terrace and moved to Stoke Newington.

His second residence came with a second woman – a wealthy Canadian TV news reporter named Nancy, who lived in Primrose Hill. This seemd to be the tipping point of Michael DeFreitas’s life. He made attempts to escape the world of the hustler, returning to the sea and becoming a sailor again, a life he loved. But after surviving numerous “attempts to put me away for robbery with violence and running a brothel”, while in Notting Hill, DeFreitas was accused of stealing a pot of paint from the dockyards (“there’s always a lot of it lying around apparently spare – and everybody takes it.”) He was sent to prison for three months and when he came out in 1963, the world had changed.

When he came out, he moved back to his old haunts in Notting Hill, now populated by a new white influx of bohemians, artists and dreamers. Alexander Trocci was devising Sigma, his collective of publishing, universities and culture; John Michell was running a hip record shop; drugs were everywhere and the kids were rebelling. Michael saw they had money, noted their relentless self-promotion, and rather liked the bullshitty nature of their work and projects – you got cash, and then delivered something…or nothing. It was just another hustle.

He started painting, and wrote poetry – his poetry more successful, largely due to his race meaning he was regarded as a tremendously desirable commodity in England: the “cool spade.” That said, Diana Athill, then chief editor at Andre Deutsch met and “disliked” Michael, saying he was “either a nut or a conman” – but against her better judgement, many years later, the firm would publish his autobiography, transcribed from interviews by a white English civil servant and sometime pornographic novel writer named John Stevenson.

As the 1960s progressed, Michael, like many black men, began attending meetings of West Indian men, where race was frequently discussed, with events in America developing a new black consciousness across the world. Eating at the Commonwealth Institute as part of the launch of a black newspaper called The Magnet, Michael heard a speech by the American Malcolm X, the leader of the Nation of Islam and then somewhat of a marginal figure. Impressed, he invited Malcolm X to dinner n Primrose Hill that night – X turned up at 10.30 and despite Michael and Nancy being concerned that he wouldn’t want to stay as Nancy was white, they started listening to music and didn’t drive him back to his hotel until 1am.

As the 1960s progressed, Michael, like many black men, began attending meetings of West Indian men, where race was frequently discussed, with events in America developing a new black consciousness across the world. Eating at the Commonwealth Institute as part of the launch of a black newspaper called The Magnet, Michael heard a speech by the American Malcolm X, the leader of the Nation of Islam and then somewhat of a marginal figure. Impressed, he invited Malcolm X to dinner n Primrose Hill that night – X turned up at 10.30 and despite Michael and Nancy being concerned that he wouldn’t want to stay as Nancy was white, they started listening to music and didn’t drive him back to his hotel until 1am.

For the remainder of Malcolm X’s British tour, Michael travelled with him. In a hotel in Birmingham, Malcolm told a receptionist to save a room “for my brother, Michael.” She took him literally, and entered the name Michael X in the reservation book. Michael swiftly adopted his new name.

Following Malcolm X’s assassination just three weeks later, Michael was profiled in the papers, portrayed as a leading light in British black nationalism and repeating Michael’s boasts that he’d been involved in organising the Notting Hill riots, had been to Russia for political meetings (he hadn’t, but he’d stopped off as a sailor to swap records and jeans for pots of caviar) and was the leader of a black British organisation which had 2000 members. With no one else at the fore, however, the article portrayed him as the voice of alternative black British culture, which led to him forming his own political group, the Radical Adjustment Action Society in 1965 (its acronym RAAS was specifically chosen as it was a Jamaican obscenity – raas claat, meaning sanitary towel.)

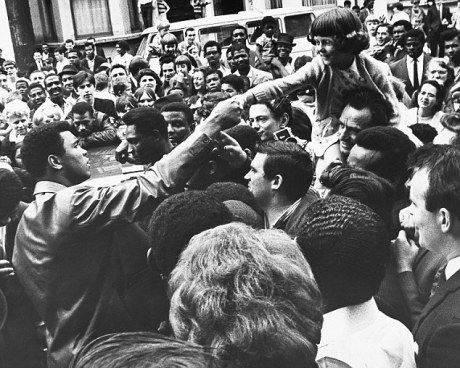

The political awakening of Michael X was still suppressed by the aggressive, somewhat childish hustler he’d always been, and his reputation ensured that he was never entirely trusted by those around him. Before long, he was on the move again – the press releases were handed to other people to write and he became interested in Islam, changing his name once again to Abdul Malik. He was still involved with the counter-culture, a key player in the London Free School (a sort of community run self-improvement centre, which Michael managed to get Muhammad Ali to visit in May 1966 when he was in the country to fight Henry Cooper at Arsenal’s Highbury stadium) and the Notting Hill Carnival (springing out of the LFS, the council said they’d only consider giving money for it if Michael wasn’t involved in any way.) He even ran the door security at the UFO at the Roundhouse, one of the few jobs he actually seems to have taken seriously and performed professionally.

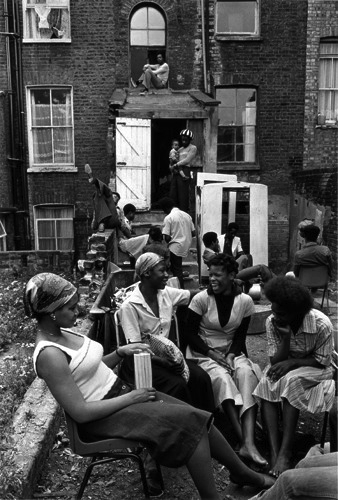

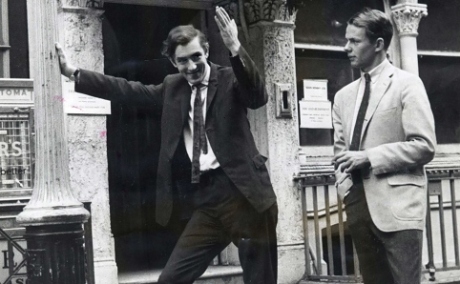

Muhammad Ali on a walkabout on the Portobello Road, Notting Hill (1966)

Muhammad Ali on a walkabout on the Portobello Road, Notting Hill (1966)

Michael continued to portray himself as Britain’s most revolutionary black leader, with a speech in Reading seeing him talk about seeing black men running away while white men beat up black women in the Notting Hill riots, telling them “if you ever see a white laying hands on a black woman, kill him immediately.” The audience laughed, but Michael was charged under new race legislation (although Enoch Powell, saying similar things, was left alone.) He was sent back to prison, serving eight months of a one-year sentence.

When he’d come out before, the world had changed.

Now when he came out, it was Michael X who’d changed. A darkness entered his life and would follow him until his early and violent death.

When he was released, he found it hard to fit in with any of the political organisations he’d been involved with, so set about creating a smaller one of his own – something small enough to maintain control over, which he could dominate and use for his own ends. Having been largely ignored by the white liberals he knew during his time in prison which had left him with “hard grudges against a lot of people”, he decided it would be a blacks-only organisation, a “arts centre cum supermarket cum alternative living space.”

The Black House represented a harder side of the late 1960s – the hippie dream of love and togetherness replaced with a venue which was founded on ideas of segregation and suspicion. And, in the days before arts councils and minority grants, it would be funded by the rich white liberals who Michael X had started to loathe.

He used heavy guilt trips, targeting white radicals, saying they should donate as a way as a form of reparation for the crimes of slavery (to squeeze money out of John Lennon, he said reparations should be paid as Lennon had stolen and commercialised black music. He got a cheque for £10,000, which most likely went straight to his own personal account.)

A warren of rooms, stretching over three shops, was rented on the Holloway Road. Crumbling Dickensian properties requiring much modernisation, the rent was about four grand a year and was paid for by the wealthy Nigel Samuel, who had been spellbound by Michael (and the constant stream of black women he was introduced to certainly helped maintain his interest in the project. Royston Casanova, the son of one of Michael’s former lovers, said of Nigel that “he loved black women. He didn’t want a white woman or a Chinese woman or whatever…black girls had him by the balls.”)

Originally named the Barter House, it became quickly known simply as the Black House.

The first part of the renovation to be carried out was Michael’s luxurious office in 1969. A kitchen and dining room followed. But while he was often photographed wearing overalls and bearing a paintbrush, he worked more on publicity than the hard graft. This included writing articles in IT Magazine:

We hope to put into what was a run-down empty shell a supermarket, a restaurant and a cultural centre where things like a cinema and theatre will happen. There we hope to show the people of the host community what we are really like through our theatre…The Black House needs new toilets, paint and chairs. A small cheque could go a long way to building this, you can help to make this tree we have planted bloom by writing a cheque immediately and sending it to us, you can also help by turning us on to some paint or folding chairs which we urgently need There is also a communal eating place where we meet daily at 1.30pm to discuss further work, you can join us here too, the food is swinging, our cook is a beautiful cat. Sit and rap with him, let him transport you into another world with his wonderful cooking and fascinating stories.

A fund-raising brochure was written by a young black South African journalist called Lionel Morrison – he pitched the Black House as a centre for disaffected black youth, where they could make music, put on plays and learn about African history. Sent to the great and good (many of whom were put off by Michael’s notoriety), an estimated £20,00 was donated, including from Muhammed Ali (who donated several thousand), Sammy Davis Jr and John Lennon.

But nothing really came of the plans. Over the next year, the money kept rolling in, but nothing changed. When the hippies came to see the new project, nothing much was happening. The Black House supermarket – intended to sell only African and West Indian goods, with an entirely black staff – missed the announced opening dates time and time again. As John L. Williams wrote in his excellent biography of Michael: “As 1969 turned into 1970, it was becoming obvious that whatever the Black House was, it was not an inspiring oasis of peace and love in the midst of grimy North London. Instead it was an intimidating establishment used as a base for various kinds of illegal activity.”

Mick Farren said it was “full of North London rudies in pork-pie hats” and Michael spoke of him and his boys building up a bank and engaging in “fighting games, rough games.” He was surrounded by hard men, usually Trinidadians: Darcus Howe called them “a group of people around him who he’d look after. Big men. Give you £40 a week or whatever, and if he tells you to chop his head off, you do it.” The salary was supposedly for the work done at the Black House, but was in actuality a fee to work as his private militia.

Michael started sending out his boys to rip off the gentle hippie drug dealers – “terrible tales were coming back of armed robbery within what had been a very, very peace-loving, city-wide hashish-dealing scene,” recalled Mick Farren. “Michael…didn’t have a legit dealing set-up, there wasn’t a smuggler supplying him, so his wasn’t a proper business, it was parasitic.”

Drugs were rife but the Black House did, however, have a set of rules, modelled loosely along the same lines as the Nation of Islam. No alcohol (although dope-smoking was allowed), and interracial sex was banned. These rules – strictly enforced, often with threats of violence against rule-breakers – ended up in “people’s courts”, where rulebreakers were dealt with interally.

Michael was becoming a dictator, ruling over an almost cult-like gathering of followers and acolytes.