Michael X and the Black House of Holloway Road

June 17, 2013

Not far from Highbury and Islington Station, numbers 95-101 Holloway Road look much like the rest of the houses stretching to either side – unloved, grubby Victorian piles with transient shops underneath: day-glo internet cafes, small lawyers specialising in immigration issues, greasy spoons which have seen better days.

Situated above the Wig and Gown pub, here’s nothing to show that, forty years ago, these houses were briefly the heart of radical black Britain.

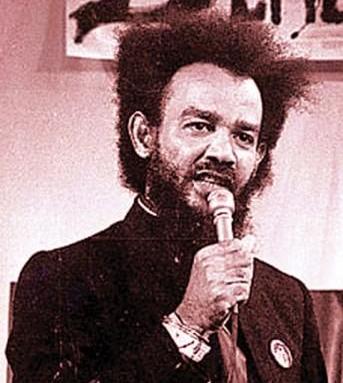

The Black House was the brainchild of Michael X, a man of many contradictions. A published author, firebrand community leader and darling of the left-leaning avant garde, he was also a pimp, conman and megalomaniac who would later be hanged for his part in two brutal murders.

Born in Trinidad in 1933, the charismatic Michael de Freitas was a seaman when he docked at Cardiff in his mid-twenties and decided to stay in Britain. With job opportunities for West Indian immigrants solely of the dogsbody variety – working in car factories or in the bus garages – he became a pimp, living off the earnings of his girlfriend, and when the relationship ended, moving onto other women.

By 1957, with Cardiff unlikely to make him his fortune, he moved to Bravington Road W9, between Kilburn and Ladbroke Grove, with a prostitute named Sandra. Like many young immigrant men with few opportunities, de Freitas found no alternative but to hustle: getting back into pimping, organising gambling rackets with limited success, and taking part in a scam stealing luggage from the West London Air Terminal in Cromwell Road.

In 1958, DeFreitas moved to Southam Street in Notting Hill with his partner Desiree.

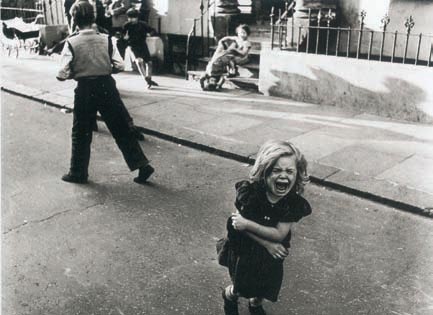

The future Labour Shadow Chancellor Alan Johnson was born in the street at the same time (his 2013 memoir This Boy tells the almost unimaginably bleak story of his childhood in this Notting Hill slum), and the photographer Roger Mayne photographed the road between 1958 and 1961.

As he wrote in his 1968 autobiography, From Michael de Freitas to Michael X:

It was impossible to believe you were in twentieth-century England: terraced houses with shabby, crumbling stonework and the last traces of discoloured paint peeling from their doors, windows broken, garbage and dirt strewn all over the road, every second house deserted, with doors nailed up and rusty corrugated iron across the window spaces, a legion of filthy white children swarming everywhere and people lying drunk across the pavement…

As Desireee told David Peace, “Southam Street was rough, but black people expected that. You were lucky you had a room and nobody bothered you if you paid your rent.”

In the Notting Hill of the 1950s, two social groups of outcasts came together: the recent West Indian immigrants and the working-class white prositutes. Larry Ford, a sometime club owner and contemporary of de Freitas, noted that “you get two outcasts, social outcasts, the blacks and the prostitutes and these two get together and the money comes in.”

In his autobiography, de Freitas wrote about a woman named Sylvia, who he acted as a pimp for (although he claimed she simply turned up with £40 one day, handed it over to him, and their working relationship began from there.) He coldly pondered his position: “People have been trying to work out why prostitutes need a ponce since the profession began and nobody’s found a satisfactory answer. In this girl’s case I think she was a compulsive giver and she had no other way of making so much to give.” Sylvia certainly found someone who would take as much as she could make.

As De Freitas pimped, he quickly became well-known on the semi-criminal scene for the long hours his girls worked (“the way they saw it was that I sent the girl out to work and allowed her to do nothing but to stay on the job constantly. In fact, of course, she seemed to want to do nothing else” he wrote, probably entirely fictionally.)

But during the summer of 1958, Notting Hill sporadically exploded in incidents of violence. Carribean men were being attacked and beaten on the streets by large groups of white men, the flames of racial hatred fanned by Oswald Moseley, the Union movement and the White Defence League, whose motto was ‘Keep Britain White.’

Outside the Calypso Club on Westbourne Park Road, a meeting was held. As three West Indians addressed the crowd, urging them to start committees and write to their MPs to protest against the indiscriminate attacks and the rising tide of racial hatred, DeFreitas asked to speak. It would be his first ‘political’ speech.

He told the crowd “You don’t need committees and representations. What you need is to get a few pieces of iron and a bit of organisation so when they come in here we can defend ourselves.” There was a roar of support and Michael led an attack on a local club used exclusively by white criminals – “some of us lobbed petrol bombs in the back of the buildings while the rest waited in ambush out front.”

Surprisingly, de Freitas didn’t think the two weeks of sporadic clashes and violence now knwon as the 1958 Brixton race riots – which he could easily have claimed a leading role in – were racially motivated. DeFreitas believed the race angle was a creation of the press – “in general people just drifted into violence, finding themselves involved without knowing how or why.” Much like the riots of 2011, he believed “there’s always a large section of any population which is attracted to riots for kicks and to relieve the boredom of their dull lives. With a few wild ones throwing bottles everyone tends to get involved.”

He thought the racial element was only introduced as “white people don’t run to the blacks for protection, nor the blacks to the whites. They separate into their own colour groups, And there you have it, created out of nothing – a race riot. Or, at least, the atmosphere of a race riot. In actual fact, there still wasn’t much real action.”

Following the unrest of the summer came a wave of left-wing, middle-class, liberal, mainly young do-gooders who flooded into the area to try and help the minority population. DeFreitas was frequently in the mix, showing parties of MPs around the “real” Notting Hill.

Around this time, he also worked for the landlord Peter Rachman, having impressed Rachman when, as a tenant, he not only took him on in a tribunal to get his rent lowered, but attempted to start an entire campaign against his empire. Refusing to be cowed by Rachman’s heavies who called round, Rachman decided to take another tact: he offered DeFreitas a job. DeFreitas took it, and Rachman went on to help him speculate in property (Michael moved into the top floor of one of the houses he bought in Colville Terrace, operated a brothel in the basement, and opened up a gaming house in the basement of a property in Powis Terrace.)

When he saw Rachman was selling off his properties, DeFreitas thought he must have some sort of insider knowledge about the market, so he sold Colville Terrace and moved to Stoke Newington.

His second residence came with a second woman – a wealthy Canadian TV news reporter named Nancy, who lived in Primrose Hill. This seemd to be the tipping point of Michael DeFreitas’s life. He made attempts to escape the world of the hustler, returning to the sea and becoming a sailor again, a life he loved. But after surviving numerous “attempts to put me away for robbery with violence and running a brothel”, while in Notting Hill, DeFreitas was accused of stealing a pot of paint from the dockyards (“there’s always a lot of it lying around apparently spare – and everybody takes it.”) He was sent to prison for three months and when he came out in 1963, the world had changed.

When he came out, he moved back to his old haunts in Notting Hill, now populated by a new white influx of bohemians, artists and dreamers. Alexander Trocci was devising Sigma, his collective of publishing, universities and culture; John Michell was running a hip record shop; drugs were everywhere and the kids were rebelling. Michael saw they had money, noted their relentless self-promotion, and rather liked the bullshitty nature of their work and projects – you got cash, and then delivered something…or nothing. It was just another hustle.

He started painting, and wrote poetry – his poetry more successful, largely due to his race meaning he was regarded as a tremendously desirable commodity in England: the “cool spade.” That said, Diana Athill, then chief editor at Andre Deutsch met and “disliked” Michael, saying he was “either a nut or a conman” – but against her better judgement, many years later, the firm would publish his autobiography, transcribed from interviews by a white English civil servant and sometime pornographic novel writer named John Stevenson.

As the 1960s progressed, Michael, like many black men, began attending meetings of West Indian men, where race was frequently discussed, with events in America developing a new black consciousness across the world. Eating at the Commonwealth Institute as part of the launch of a black newspaper called The Magnet, Michael heard a speech by the American Malcolm X, the leader of the Nation of Islam and then somewhat of a marginal figure. Impressed, he invited Malcolm X to dinner n Primrose Hill that night – X turned up at 10.30 and despite Michael and Nancy being concerned that he wouldn’t want to stay as Nancy was white, they started listening to music and didn’t drive him back to his hotel until 1am.

As the 1960s progressed, Michael, like many black men, began attending meetings of West Indian men, where race was frequently discussed, with events in America developing a new black consciousness across the world. Eating at the Commonwealth Institute as part of the launch of a black newspaper called The Magnet, Michael heard a speech by the American Malcolm X, the leader of the Nation of Islam and then somewhat of a marginal figure. Impressed, he invited Malcolm X to dinner n Primrose Hill that night – X turned up at 10.30 and despite Michael and Nancy being concerned that he wouldn’t want to stay as Nancy was white, they started listening to music and didn’t drive him back to his hotel until 1am.

For the remainder of Malcolm X’s British tour, Michael travelled with him. In a hotel in Birmingham, Malcolm told a receptionist to save a room “for my brother, Michael.” She took him literally, and entered the name Michael X in the reservation book. Michael swiftly adopted his new name.

Following Malcolm X’s assassination just three weeks later, Michael was profiled in the papers, portrayed as a leading light in British black nationalism and repeating Michael’s boasts that he’d been involved in organising the Notting Hill riots, had been to Russia for political meetings (he hadn’t, but he’d stopped off as a sailor to swap records and jeans for pots of caviar) and was the leader of a black British organisation which had 2000 members. With no one else at the fore, however, the article portrayed him as the voice of alternative black British culture, which led to him forming his own political group, the Radical Adjustment Action Society in 1965 (its acronym RAAS was specifically chosen as it was a Jamaican obscenity – raas claat, meaning sanitary towel.)

The political awakening of Michael X was still suppressed by the aggressive, somewhat childish hustler he’d always been, and his reputation ensured that he was never entirely trusted by those around him. Before long, he was on the move again – the press releases were handed to other people to write and he became interested in Islam, changing his name once again to Abdul Malik. He was still involved with the counter-culture, a key player in the London Free School (a sort of community run self-improvement centre, which Michael managed to get Muhammad Ali to visit in May 1966 when he was in the country to fight Henry Cooper at Arsenal’s Highbury stadium) and the Notting Hill Carnival (springing out of the LFS, the council said they’d only consider giving money for it if Michael wasn’t involved in any way.) He even ran the door security at the UFO at the Roundhouse, one of the few jobs he actually seems to have taken seriously and performed professionally.

Muhammad Ali on a walkabout on the Portobello Road, Notting Hill (1966)

Muhammad Ali on a walkabout on the Portobello Road, Notting Hill (1966)

Michael continued to portray himself as Britain’s most revolutionary black leader, with a speech in Reading seeing him talk about seeing black men running away while white men beat up black women in the Notting Hill riots, telling them “if you ever see a white laying hands on a black woman, kill him immediately.” The audience laughed, but Michael was charged under new race legislation (although Enoch Powell, saying similar things, was left alone.) He was sent back to prison, serving eight months of a one-year sentence.

When he’d come out before, the world had changed.

Now when he came out, it was Michael X who’d changed. A darkness entered his life and would follow him until his early and violent death.

When he was released, he found it hard to fit in with any of the political organisations he’d been involved with, so set about creating a smaller one of his own – something small enough to maintain control over, which he could dominate and use for his own ends. Having been largely ignored by the white liberals he knew during his time in prison which had left him with “hard grudges against a lot of people”, he decided it would be a blacks-only organisation, a “arts centre cum supermarket cum alternative living space.”

The Black House represented a harder side of the late 1960s – the hippie dream of love and togetherness replaced with a venue which was founded on ideas of segregation and suspicion. And, in the days before arts councils and minority grants, it would be funded by the rich white liberals who Michael X had started to loathe.

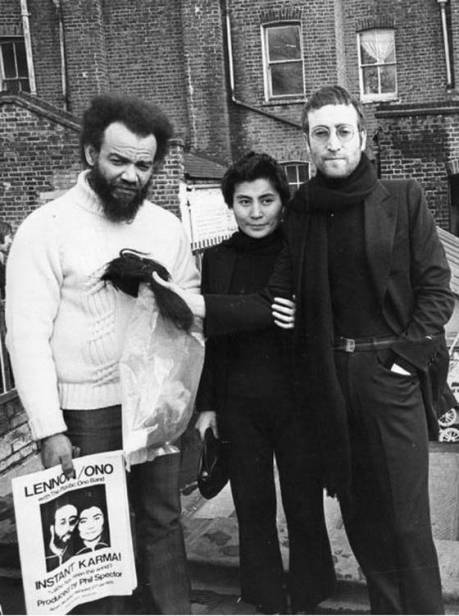

He used heavy guilt trips, targeting white radicals, saying they should donate as a way as a form of reparation for the crimes of slavery (to squeeze money out of John Lennon, he said reparations should be paid as Lennon had stolen and commercialised black music. He got a cheque for £10,000, which most likely went straight to his own personal account.)

A warren of rooms, stretching over three shops, was rented on the Holloway Road. Crumbling Dickensian properties requiring much modernisation, the rent was about four grand a year and was paid for by the wealthy Nigel Samuel, who had been spellbound by Michael (and the constant stream of black women he was introduced to certainly helped maintain his interest in the project. Royston Casanova, the son of one of Michael’s former lovers, said of Nigel that “he loved black women. He didn’t want a white woman or a Chinese woman or whatever…black girls had him by the balls.”)

Originally named the Barter House, it became quickly known simply as the Black House.

The first part of the renovation to be carried out was Michael’s luxurious office in 1969. A kitchen and dining room followed. But while he was often photographed wearing overalls and bearing a paintbrush, he worked more on publicity than the hard graft. This included writing articles in IT Magazine:

We hope to put into what was a run-down empty shell a supermarket, a restaurant and a cultural centre where things like a cinema and theatre will happen. There we hope to show the people of the host community what we are really like through our theatre…The Black House needs new toilets, paint and chairs. A small cheque could go a long way to building this, you can help to make this tree we have planted bloom by writing a cheque immediately and sending it to us, you can also help by turning us on to some paint or folding chairs which we urgently need There is also a communal eating place where we meet daily at 1.30pm to discuss further work, you can join us here too, the food is swinging, our cook is a beautiful cat. Sit and rap with him, let him transport you into another world with his wonderful cooking and fascinating stories.

A fund-raising brochure was written by a young black South African journalist called Lionel Morrison – he pitched the Black House as a centre for disaffected black youth, where they could make music, put on plays and learn about African history. Sent to the great and good (many of whom were put off by Michael’s notoriety), an estimated £20,00 was donated, including from Muhammed Ali (who donated several thousand), Sammy Davis Jr and John Lennon.

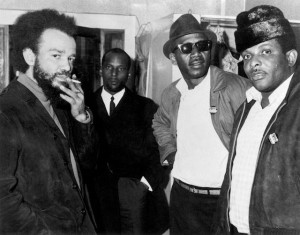

But nothing really came of the plans. Over the next year, the money kept rolling in, but nothing changed. When the hippies came to see the new project, nothing much was happening. The Black House supermarket – intended to sell only African and West Indian goods, with an entirely black staff – missed the announced opening dates time and time again. As John L. Williams wrote in his excellent biography of Michael: “As 1969 turned into 1970, it was becoming obvious that whatever the Black House was, it was not an inspiring oasis of peace and love in the midst of grimy North London. Instead it was an intimidating establishment used as a base for various kinds of illegal activity.”

Mick Farren said it was “full of North London rudies in pork-pie hats” and Michael spoke of him and his boys building up a bank and engaging in “fighting games, rough games.” He was surrounded by hard men, usually Trinidadians: Darcus Howe called them “a group of people around him who he’d look after. Big men. Give you £40 a week or whatever, and if he tells you to chop his head off, you do it.” The salary was supposedly for the work done at the Black House, but was in actuality a fee to work as his private militia.

Michael started sending out his boys to rip off the gentle hippie drug dealers – “terrible tales were coming back of armed robbery within what had been a very, very peace-loving, city-wide hashish-dealing scene,” recalled Mick Farren. “Michael…didn’t have a legit dealing set-up, there wasn’t a smuggler supplying him, so his wasn’t a proper business, it was parasitic.”

Drugs were rife but the Black House did, however, have a set of rules, modelled loosely along the same lines as the Nation of Islam. No alcohol (although dope-smoking was allowed), and interracial sex was banned. These rules – strictly enforced, often with threats of violence against rule-breakers – ended up in “people’s courts”, where rulebreakers were dealt with interally.

Michael was becoming a dictator, ruling over an almost cult-like gathering of followers and acolytes.

On 4 February 1970, Lennon and Yoko Ono popped by for a strange publicity stunt, where they arrived with newly shorn heads and a bag of their own hair, which they swapped for Michael’s bloodied Muhammed Ali shorts on the roof of the Black House.

The shorts were to be auctioned to raise money for world peace; the hair for funds for the Black House. As John L. Williams notes, “So baffling was this event, and so dubious was Michael’s reputation by this point, that this was the first Beatles-related publicity exercise to receive no coverage whatever in the national press.”

The following day, Lennon appeared with Michael on The Simon Dee television show. Lennon revealed that Sotheby’s declined to sell the hair because “they only sell art”. Michael’s plan to raise funds had taken another knock at the hands of the establishment.

In April 1970, there was no need to raise any more funds as an incident would lead to the house’s total collapse.

A young black American actor called Leroy House had been to work at a central London cleaning agency, but after various deductions the pay he received was less than he was expecting. Hearing the complaint, Michael assembled three men from the Black House and went to Clean-A-Flat cleaning company in Newburgh Street. They demanded £3 from the owner, 25-year-old Marvin Brown, and when he said he didn’t have any money on him, Michael picked up a bunch of files from his desk and said he could have them back if he came to the Black House with the £3. Brown called the police, and they headed down to the Black House.

Backed up by some 25 Black House regulars, Michael told the police to leave as they didn’t have a warrant. Left alone, Brown decided to pay the £3. Instead, Michael told him to come back in 30 minutes, and when he did, a court was assembled – some 30 black men and black and white women – and demanded Brown make amends for the way black people had been treated throughour history. Brown protested that as a Jew, he was also part of a persecuted minority – but no-one was impressed by this. Instead, they put a spiked slave collar (part of the Black House’s ‘museum’ of historical artefacts) on Brown, and marched him round the room until he burst into tears. When some of the women protested, his ordeal stopped and he was given his files back, but Michael then wanted him to pay a fine for bringing the police with him. Brown handed over all the money he had with him – £13. Michael have him back £8 and a signed copy of his autobiography (which he usually sold to guilty liberals at £5 a time.) He was then released. The police were waiting outside and Brown told them about his ordeal.

A week later, 50 policemen burst into the Black House and arrested everyone who’d been there during the original raid on Brown’s office. All facing trial, Michael decided to flee to Trinidad – he hated prison, and it was likely his notoriety would only give him a longer sentence than otherwise.

Additionally, the Black House was in an even worse condition than it was when it had first been taken over. The Black House had become a mixture of halfway house for black people and a youth club, with reggae club nights attracting hundreds of youths, stopped by police after complaints from the neighbours. While it was being vandalised by kids, Michael began practising Obeah, the voodoo he watched his mother performing while a child. Exorcisms were performed at the house, and residents were given amulets to wear – all of which added to the general air of paranoia and fear.

“When I saw what the Black House was about I became interested,” said Stanley Abbott, a community minded individual who was involved with the Black House at the very end, just before Michael abandoned it. “The Black House was no sinister den of sin. To me and thousands of black people in England in represented a place black youths could go. Inside the Black House was a community centre. There was amplifiers and loudspeakers, and the kids – hundreds of kids – used to play records and dance together. There were three kitchens in the Black House where the kids used to experiment with cooking. There was a library where one could go and read. I took an interest in the kids and helped them.”

The Black House finally closed in the autumn of 1970. Michael blamed its failure on the laziness of the inhabitants and resigned from all his posts within the Black Power movement – in effect, he handed the Black House and its mountain of unpaid debts to the remaining residents. There were solid, hard-working black people at the Black House, like Abbott, but just three weeks after Michael resigned, they folded in the face of the hustlers and hoods who dominated the Black House and the enterprise closed down for good.

In early February 1971, an increasingly crazed Michael X was back in Trinidad. By 1972, he’d been found guilty of the entirely senseless murder of Joseph Skeritt, a handyman who’d worked on a projected commune which was falling to pieces around him, and he was implicit (although never tried) in the murder of Gail Benson, the daughter of Tory MP Leonard Plugge. Benson had arrived at Michael’s proposed commune with her lover Hakim Jamal, an American cousin of Malcolm X (who came to believe he was God and was later murdered in the USA) and had been murdered for reasons that are entirely unclear. Michael deFreitas – aka Michael X – was hanged in May 1975.

The Black House lived on briefly in another form: about a mile up the road, a dynamic Caribbean immigrant called Herman Edwards set up ‘Harambee’ (the Swahili for ‘pulling together’) to provide a halfway house for vulnerable young people who had been in trouble with the law. Due to its similarities with Michael X’s organisation – in that it was intended to benefit the local black community and was located on the Holloway Road, not that it was in anyway a front for illegal activities – the press came to also refer to it as The Black House.

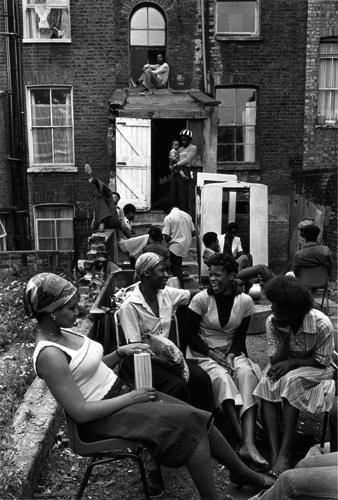

Funded by Islington Council, this second Black House lasted until the mid-1970s and was photographed extensively by Colin Jones in 1973. A book of his beautiful photographs was published in 2005.

Notes for this entry came primarily from Michael X: A Life in Black and White by John L. Williams, a tremendous read which is available here.

Colin Jones’ The Black House is also recommended and can be purchased here.

Both links take you to Abebooks, which, while owned by Amazon, support smaller booksellers – I have no affiliation with them or the site, but they’re my bookseller of choice.