Peter Cook’s The Establishment Club

March 11, 2013

Between 1961 and 1964, 18 Greek Street, Soho was the home of the Establishment Club.

The club was open for a little over three years, and for nearly half that time, the man most associated with it, Peter Cook, wasn’t even in the country. Very few photographs of its interior exist and not many recordings were made of the acts who took to its stage.

And yet, nearly fifty years after it shut, it remains one of the most iconic comedy venues in the world.

Opening a satirical nightclub had been a dream of Cook’s ever since he started performing at university. With the satire boom catapulting him into sudden stardom (he was starring nightly in Beyond The Fringe at the Fortune Theatre from May 1961), he wasted no time in setting up a joint venture with Cambridge colleague Nick Luard. His plan was to open a theatre/dinner club with a jazz club in the basement, which would feature a nightly satirical show on stage. “I didn’t think it was a risk at all,’ he later told Clive James. “My dread in my last year in Cambridge was that somebody else would have this very obvious idea to do political cabaret uncensored by the Lord Chamberlain. I thought it was a certainty.”

The flagrantly ironic name (‘the only good title that I ever thought of’, Cook famously said) came first; locating the premises second.

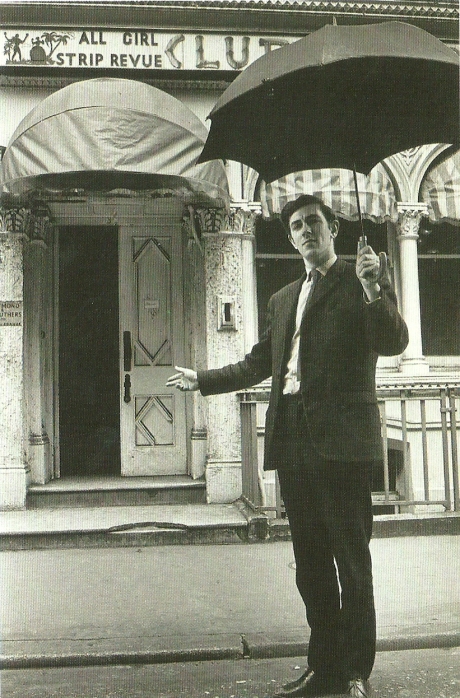

Cook himself wanted the seediness of Soho. At the time, Soho was the only place in England where sex was visibly on sale – in blue cinemas, strip joints, peep shows and stag clubs. An ongoing gangland turf war had been inflamed by the results of the Wolfenden Report, which had forced prostitutes off the streets and into the network of tiny rooms in the surrounding buildings.

On their first viewing of 18 Greek Street (then Club Tropicana, a club boasting an “all girl strip revue”), Cook’s wife Wendy recalled it was “the seediest of beer-sodden atmospheres. The windows were swagged in oceans of red velvet curtains…there were discarded G-strings, used condoms, plastic chandeliers – all the tawdry remnants of a former strip club.” It was perfect.

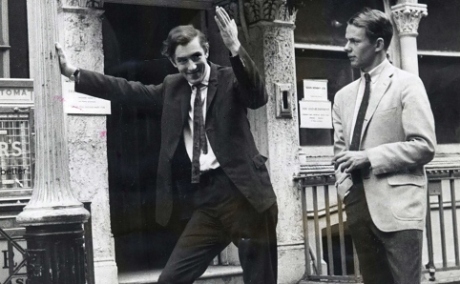

Cook and Luard at their new premises in Soho, 1961

The Establishment Club opened in October 1961. The décor was chosen by Sean Kenny, who had designed the sets for Lionel Bart’s Oliver and Roger Law (who, as one half of Fluck and Law, would go on to create the long running ITV satire puppet show Spitting Image) had a space for a nightly cartoon on one of the walls near the entrance.

The size of the place – “it was a tiny little room” recalled resident singer Jean Hart – meant it always seemed busy and intimate. Manager Bruce Copp recalled the layout: “There was a long approach as you went into the club; it was a long building, in fact, as most are on Greek Street. A good half of it was given over to the theatre and restaurant and the stage was at the far end of that. The first half was a long bar. As you came in the door, the bar used to be very crowded and yet you would recognise every face.”

Advance subscriptions had ensured there was a profit before the doors ever opened, and within weeks, membership applications quickly rose to 7000. Lifetime members received a portrait of Harold Macmillan.

Early visitors included EM Forster, the writer James Baldwin, Robert Mitchum, Jack Lemmon, Paul McCartney (on the cusp of fame) and George Melly, who visited almost nightly and had his own table kept permanently aside for him and wife Diana. The Club’s success in attracting members quickly became a double-edged sword: it was full most nights, but that meant many members couldn’t get in.

Cook on stage at the club, 1961

Some less welcome visitors also came through the doors early on – a group of local thugs turned up to innocently ask if the club had “fire insurance.” “Once, Peter brought them all in and threatened to put them all on stage. I thought that was absolutely brilliant,” recalled Christopher Logue, whose lyrics were sung at the club by Jean Hart. “Of course, they became terribly embarrassed and left.”

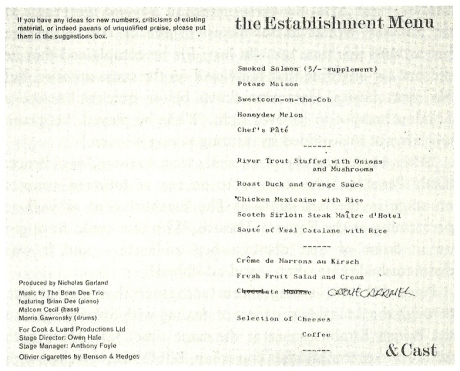

There was a first sitting in restaurant at 7.30pm before the early show started at 8.15pm. All the plates were cleared away before the show began – to avoid any “clatter and carry-on”, in the words of Bruce Copp. “The show comes first, and if they can’t wait, they are philistine and they will have to go. If they have come here just for the food, they must be mad.”

The menu from the Establishment

The show lasted for roughly 90 minutes, followed by a second sitting at the restaurant, and then the late show which started at 10.45pm. Dudley Moore, performing with Cook in Beyond The Fringe, would arrive and head downstairs around this time to perform with his Trio (he later complained he never got to see anything which happened upstairs in all the time he was there.) Cook also arrived at the same time, doing usually ten to fifteen minutes on stage every night.

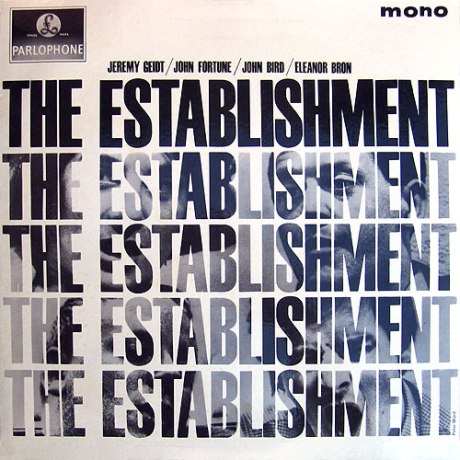

The original Establishment Club players consisted of John Bird, John Fortune, Eleanor Bron and Jeremy Geidt – near-contemporaries of Cook’s from Cambridge and, like the Beyond The Fringe performers, had been involved with Oxbridge revues. A compilation of their best sketches, recorded in the club, was released on LP (it’s currently unavailable.)

The satirical magazine Private Eye briefly moved in upstairs (prior to Cook becoming the main shareholder, although he had already given them some financial assistance on occasion) – the opening of the club and the first publication of the magazine had occured within three weeks of each other. Upstairs Sean Kenny also had a studio, as did photographer Lewis Morley (it was on the first floor of the building where he took his famous photograph of Christine Keeler astride an Arne Jacobsen chair, which you can see here at the V&A’s website, along with an interview about the session from Morley.)

In 1962, the club saw three very different comedians perform landmark gigs.

The American comedian Lenny Bruce did his first and only London run at the club. Cook personally picked him up from Heathrow and the early signs weren’t good: “This dreadful shambling figure came out carrying three miniature tape recorders, which he insisted on playing all the way and which consisted of nothing but aeroplane noises and grunting and farting. And I thought, “What am I going to do with this wreck?” I had left him at the hotel, and the next thing that happened was that I got a call saying Mr Bruce had been asked to leave the hotel because there were hookers and syringes everywhere.”

Bruce endured a terrible week, struggling through the days as the only heroin he could illegally find in London was far weaker than the stuff he was legally prescribed in the US. Jean Hart recalled, “I sang a couple of nights when Lenny Bruce was there and it was awful. This creature was almost being eaten up. He was huddled in the corner like a little rag doll…nobody knew how to deal with this man whose habit was a hundred times bigger than anything our doctors had seen. He was going crazy, poor man.”

His material included the difficulty of getting snot off suede jackets, cancer, and asking the front row “Hands up who has masturbated today?” Christopher Booker remembered, “I loved it, but I was slightly worried by the atmosphere of the time; the menace of it. I went almost every night Lenny Bruce was there.”

Bizarrely, the singer Alma Cogan became smitten with Bruce, and attended every night of his run. Bruce didn’t reciprocate her affections – he spent most nights in the greasy spoon cafes around Leicester Square, which he liked because they reminded him of his early days in New York.

A return booking in May 1963 fell apart when the Home Secretary deemed Bruce an “undesirable alien” and he was refused entry to the country as soon as he reached Heathrow.

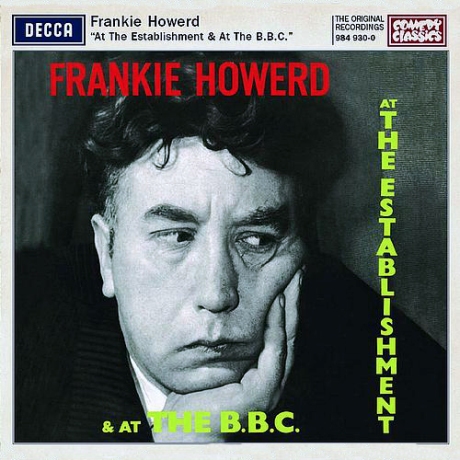

A similarly seismic performance came from a comedian who couldn’t be any less like Lenny Bruce: Frankie Howerd.

Hugely popular in the post-World War 2 period, Howerd’s career was largely regarded as being on the wane when he attended the Evening Standard Theatre Awards at the Savoy. Given the chance to say a few words (and his terrible nerves fortified by scotch), he brought the house down. Cook was in the audience and he immediately booked him to play the Establishment Club. On Howerd’s This Is Your Life many years later, Cook called him “one of the funniest men in the world. I’d say ‘the funniest’, but Dudley’s very sensitive.”

Cook also thought the irreverent Howerd might be a big name to attract new members. Howerd was paid £400 a week, and his act was written by a who’s who of comedy – Johnny Speight (author of Till Death Us Do Part) wrote the main bulk of the material, with contributions from Galton and Simpson (the writers of Hancock’s Half Hour), and Howerd had the routine checked over by Barry Cryer, Barry Took and Eric Sykes. He couldn’t afford for it to go badly. It didn’t.

His opening line – “If you expect Lenny Bruce then you may as well piss off now!” – brought the house down. He continued by pondering why a sausage was funnier than a lamb chop. His performances packed the club out. On the LP released of the act, Kenneth William’s instantly recognisable laugh can be heard throughout, and also in the audience was Ned Sherrin who was so impressed, he gave Howerd a lengthy solo slot on That Was The Week That Was. A star was reborn.

The Australian actor and comedian Barry Humpheries also made his debut at the Establishment in 1962 – although the reception was far less rapturous than it was for Howerd or Bruce. This Lewis Morley photo shows Humpheries relaxing outside the club in 1962.

The Australian actor and comedian Barry Humpheries also made his debut at the Establishment in 1962 – although the reception was far less rapturous than it was for Howerd or Bruce. This Lewis Morley photo shows Humpheries relaxing outside the club in 1962.

Humpheries had served for a year as Sowerberry the Undertaker in Oliver, understudying Ron Moody’s Fagin, and was feeling creatively stifled. Having returned to Melbourne earlier in the year for his critically acclaimed first solo show (A Nice Night’s Entertainment, largely a showcase for his Melbourne housewife Dame Edna Everage) he remained an underground figure on the fringes of art and theatre in England. In May 1962, Peter Cook asked Humpheries to stand in for Lenny Bruce when the British authorities refused to let him enter the country.

Humpheries recalled first meeting Cook outside the club in Edna’s 1989 autobiography My Gorgeous Life. He had “a little upside-down smile, like a thin, kind shark.” After“some university students…doing impressions of Harold Macmillian and stopping to laugh at themselves and light smelly cigarettes,” Humpheries stepped onto the Establishment stage and began “his endless chatter.”

That evening the little tables in the club were packed with celebrities, and kind, supportive Peter pointed some of them out to me as we nibbled our steaks in the corner. That jolly little balding man with the wavy upper lip was John Betjeman, the famous poet, who apparently adored me. Over there in a grubby pink suit was a droopy man whose arms were too long for his body, chain smoking cigarettes with the wrong fingers. His name was Tynan, a critic apparently…Jean Shrimpton, the famous glamour-puss, was looking bewildered. Holding forth at her table was a carrot-headed camel-faced man in a crumpled corduroy suit called Dr [Jonathan] Miller, who seemed to be trying to knot his arms together with some degree of success. I even noticed a few journalists with notebooks at the ready.

As Humpheries droned on, he became aware the laughter he’d heard in Australia was entirely absent. “Instead of laughter and applause, I could hear an odd shuffling and clattering noise and even the sound of people chatting quite loudly amongst themselves.”

As Humpheries droned on, he became aware the laughter he’d heard in Australia was entirely absent. “Instead of laughter and applause, I could hear an odd shuffling and clattering noise and even the sound of people chatting quite loudly amongst themselves.”

The act was a flop, and the critics were harsh. The Daily Mail reviewed the gig: “His eyes tiny like diamond chips, his mouth slit and thin like a beak, Barry Humpheries looked for all the world like an emu in moult.”

Humpheries later referred to his “highly successful, five minute season” at the Establishment Club. Continuing his dramatic and musical roles, he created Barry McKenzie for Private Eye in 1964 (which ran for a decade and spawned two movies in the early 1970s) before a triumphant return to Australia with the 1965 solo show Excuse I. Success in Britain eluded him until 1976’s Housewife Superstar! which became “one of the most popular series of one-man shows since Charles Dickens’ tours in the 1880s.” Edna – “the thinking man’s Eva Peron” – played to sold out audiences for four months, first at the Apollo, then the Globe. From that point on he was a West End fixture.

In September 1962, Cook sailed to New York with the rest of the Beyond The Fringe cast to start the show on Broadway. Just as it had been in London, the show was a huge success – as Harold MacMillan had attended the London run, so JFK turned up for a performance in New York. Cook also opened up a US version of The Establishment at the Strollers Theatre Club on East 54th St.

By the time Cook returned to London in April 1964, the Establishment Club was going down the tubes. It had run into serious financial trouble. As Luard ran into financial difficulties when a couple of his other businesses folded, he was forced by the bank to hand the club over to Raymond Nash, a “tough Lebanese entrepreneur” and stockholder who craved both legitimacy (the Establishment was an entirely straight business, something of a rarity in Soho.) Nash took over the running of the Establishment and it was the moment everything changed – in short, the intelligentsia stopped going.

Luard’s wife Elizabeth said “The collapse of the enterprise was sudden. Peter and Nicholas never, to my knowledge, discussed it – still less apportioned blame. Certainly Nicolas blamed himself; and perhaps Peter knew that he’d left his friend up the creek without a paddle.”

Since 1964, 18 Greek Street has been much the same as it is today – a bar with nightclub leanings. Formerly the Boardwalk, the occupier since 2008 has been the “funky cocktail bar and restaurant” Zebrano. Zebrano even paid quiet tribute to the former club by naming themselves “Zebrano at the Establishment” over one window.

On 15 February 2009, a plaque was erected outside, commemorating the Establishment. It was unveiled by the DJ Mike Read – it was going to be Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees, but he pulled out when a newspaper revealed he’d fathered a child with his housekeeper.

In September 2012, Keith Allen and Victor Lewis-Smith attempted to revive the spirit of the Establishment Club with two nights of comedy and cabaret at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club on Gerrard Street. The evenings were planned as monthly pop-ups, following a conversation Lewis-Smith had with Cook’s widow Lin, where she claimed Cook was planning to reopen The Establishment when he died in 1995. Whether they will manage to get back into the original premises remains to be seen.

Note: there’s actually surprisingly little specific material on the Establishment Club in books dealing with satire. Most of the anecdotes are simply people saying “Gosh, yes, I remember it, it was frightfully exciting.” One of the more detailed books is Wendy Cook’s So Farewell Then: The Biography of Peter Cook, which I used alongside all the other major Cook books. Any more details gratefully received.